On Sundays during Lent, there is the Liturgy of St. Basil the Great, which differs from the usual Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. One particularly notable difference for a worshiper is the replacement of the chant It Is Truly Meet by All Creation Rejoiceth in Thee (Tone 8). The text of this hymn is found in Octoechos, and there is a special remark that says, “We sing it not sitting but standing, and with fear and awe”.

The author of this hymn is St. John of Damascus (8th century). This text was first recorded in the Liturgy of St. Basil in Russia only in the 17th century in the Moscow Sluzhebnik of 1602. Here is the full text of this hymn:

All of Creation rejoiceth in thee, O full of grace:

the angels in heaven and the race of men,

O sanctified temple and spiritual paradise,

the glory of virgins, of whom God was incarnate

and became a child, our God before the ages.

He made thy body into a throne,

and thy womb more spacious than the heavens.

All of creation rejoiceth in thee, O full of grace:

Glory be to thee.

This chant glorifies the Mother of God, Her liturgical and universal significance. She is likened to the Church and the Paradise, because the Baby She gave birth to is the Savior of the world.

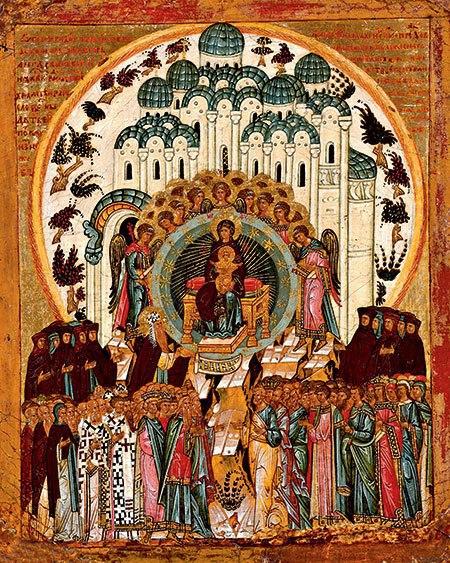

The lines of this beautiful hymn are reflected in Russian iconography – the first icons titled All Creation Rejoiceth in Thee date back to the late 15th and early 16th centuries. These icons figuratively embody the idea of the unity of the universe: the world above, enclosed in a circular symbol of eternal harmony, and the earthly world at the foot of the mountain. Even the rounded lines that dominate the composition of the icons correspond to the circularity of the text that is formed by repeating the first line at the end. For example, a Novgorod image depicts a cathedral (“sanctified temple”) on a white background with trees – the traditional iconographic representation of paradise (“spiritual paradise”). The center and meaning of the entire composition, as well as the hymns, is the Virgin Mary sitting on the throne, surrounded by radiant glory, with the Baby in her arms (“of whom God was incarnate and became a child”), and around her there are angels (“angels in heaven”). There are two groups of nuns on the right and on the left. Below there are all the orders of holiness: forefathers, prophets, apostles, saints, martyrs, etc. – in accordance with the text of the secret supplication prayer, which is recited in the altar by the priest, while the choir performs the hymn. John of Damascus is the closest to the Virgin Mary – he hands Mary the scroll with his text.

Ferapontov Monastery paintings, which date back to the early 16th century, include many “hymnal” compositions, emphasizing the inextricable link between worship and iconography. In addition to the scenes from the Akathist of the Most Holy Mother of God, there is also the first composition illustrating the prayer All Creation Rejoiceth in Thee, which, thanks to its colorful and stylistic depiction of the figures, is imbued with jubilant festivity and joyful glorification of the Most Holy Mother of God.

New iconography in medieval Russian art could not arise apart from the existing traditional forms. The Mother of God with the Child on the Throne, the Garden of Eden, groups of people according to the ranks of holiness, the Archangels – all these are found in the church sites of Byzantium and the Slavic lands. Their consolidation into a new composition titled All Creation Rejoiceth in Thee belongs to Russian icon painters. The principal novelty of the decision is first of all that icon painters managed to render the profound philosophical idea arising from the meaning of the Divine Liturgy figuratively.

This scene was very popular later, chiefly due to its universality. The only things that changed were the shape of the temple, the depiction of the paradise trees, the selection of saints, but the harmonious balance between the terrestrial and the celestial remained unaltered, figuratively conveying the central meaning of the chant. More than twenty large All Creation Rejoiceth in Thee icons of the 17th century and a few smaller ones have survived.

Very glad to see this. We have a space for iconography above our kliros, and I am wondering where icons such as these are often found in the church architecture. The space we have does not really fit a round shape, it is a long horizontal area. We have also been looking at icons of the Heavenly Hosts. Thank you for posting!

Dear Anne, you are so welcome! God bless!

Thank you for the excellent explanation of how the Liturgy of St. Basil the Great informed this icon. It is fascinating to me to see how our worship manifests itself in a variety of ways.

You are so welcome! God bless!