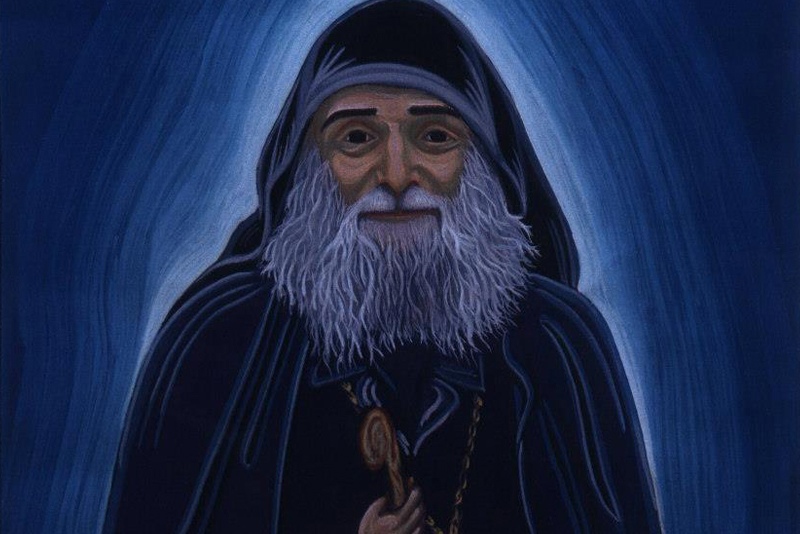

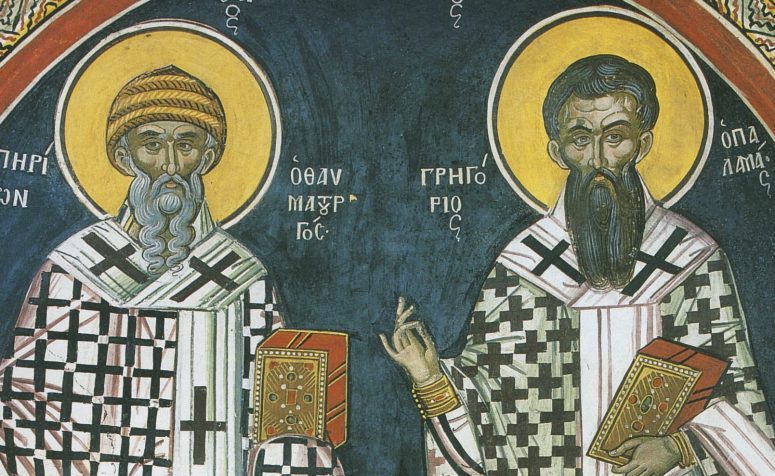

We commemorate the great theologian and monk Saint Gregory Palamas on the second Sunday of the Great Lent. When we mention the name of this saint – even if we don’t know much about him – we immediately recall the Tabor Light and his teaching of the participation of a human being in the Uncreated Grace – the Orthodox doctrine of theosis. Who was that man? What was his life like? Let’s recall several fun facts from St. Gregory’s biography.

1. The future holy hierarch was born in 1296 to a noble family who lived in Asia Minor (now Turkey). His family had to flee to Greece due to a Turkish invasion. Thus, hundreds of thousands of Greeks who had to leave their homeland and their homes in the 1920s literally repeated this episode of St. Gregory’s life.

2. The future champion of hesychasm grew at the court of Emperor Andronicus II Palaiologos who, in spite of being a mediocre politician, was a pious man and did a lot to further the idea of the symphony between the Church and the State. Perhaps, the future holy hierarch chose to become a monk under the influence of his father, whose profound godliness is proved by the following amazing story. During a session of the Senate, Emperor Andronicus gave the floor to the future saint’s father but the latter was so engrossed in prayer that he didn’t hear the question. Andronicus didn’t want to interrupt the honorable man’s prayer and didn’t insist on getting an answer!

3. Gregory Palamas received a formidable education in secular sciences and philosophy. He knew a lot about Aristotle and believed that the study of logic was useful and appropriate for a Christian. At the same time, Gregory, like many Christians of his time, denied and refused to study Plato’s metaphysics because of its incompatibility with Christianity. Gregory was proud of rejecting Plato’s philosophy.

4. As a result of his visit to some monks in Constantinople around 1316, Gregory unexpectedly decided to commit himself to monasticism. Gregory was influenced by Saint Theoliptus of Philadelphia who taught him ‘the pure prayer’. In spite of the emperor’s pleas and promises of a brilliant career, he remained adamant. Palamas’ father had been tonsured before his death when Gregory was in his teens, so the young man was responsible for his large family. Gregory decided to do away with all family-related obstacles to his tonsure using a method, typical of medieval Byzantium: he suggested that his mother, his two sisters, two brothers, and numerous servants become monastics, too, which they all did. His sisters and his mother became nuns and remained in Constantinople, while Gregory and his two brothers left for Mt. Athos where Gregory spent twenty years.

5. It is interesting to mention the fact that Palamas was in favor of a semi-communal monastic lifestyle, which combined elements of coenobitic living introduced to Athos by St. Athanasius in the 10th century and secluded eremitic living that originated in St. Anthony the Great times. Therefore, Palamas aimed to avoid both strict discipline and accumulation of material wealth by big monasteries and excessive spiritualism and pronounced individualism of hermits. It must be noted that Palamas criticized immoderate hesychasm, especially if it led to neglect of liturgical life of the Church and participation in the Sacraments. That was why Gregory would spend some time in big coenobitic monasteries from time to time.

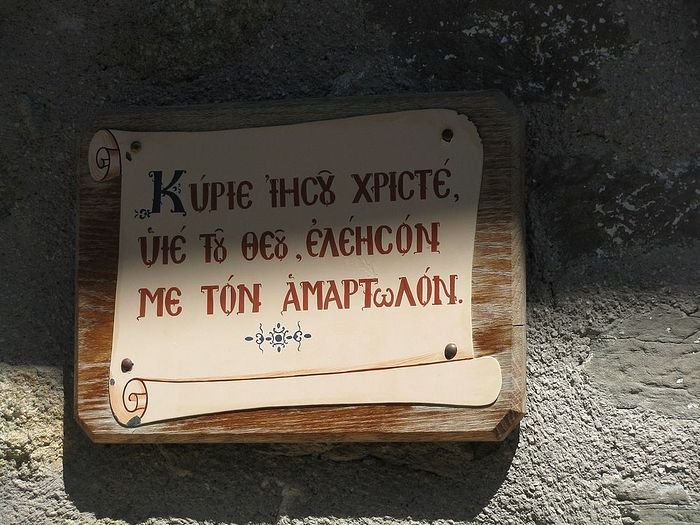

6. Wishing to devote himself more fully to prayer and asceticism he entered a skete called Glossia, where he lived under the supervision of a great ascetic named Gregory. Unfortunately, due to frequent pirate raids he was compelled to leave the skete and went to the Holy Land. However, God had a different plan for him. Gregory made it to Thessalonica where he was ordained a presbyter at the age of 30. He joined a spiritual circle led by Isidore, who was a disciple of Gregory the Sinaite and the future Patriarch of Constantinople. Isidore and Gregory devoted themselves to social outreach because, like St. Symeon the New Theologian and Theoliptus of Philadelphia, they did not regard hesychast spirituality as the exclusive property of monks. They took to spreading Jesus Prayer beyond monasteries’ walls, believing that this practice of prayer was helpful for making the grace of Baptism real and powerful. Gregory founded a skete not far from Veria where he spent five years doing ascetic practices, joining other monks only on Saturdays and Sundays to take part in the Liturgy and conversation. His way of living was interrupted only once when he had to travel to Constantinople to attend his mother’s funeral.

7. During his heated discussions with Barlaam and later with his former disciple Akindynos who rejected the possibility of direct vision and participation in God’s Glory, Gregory invariably defended the Orthodox practice of mindful prayer and hesychasm, justly concluding that it was a logical outcome and a genuine spiritual experience of the mystery of the Incarnation of God and the possibility of man’s theosis. Gregory was thrown in prison for his views by Patriarch John Kalekas and even excommunicated, which didn’t prevent him from writing treatises defending the proper Orthodox doctrine. A Synod of 1347 defrocked Patriarch John, and Gregory was appointed the bishop of Thessalonica in the same year. This period of his ministry was marked by illustrious sermons against social injustice, which, in spite of their apparently clear language, never lacked theological content and were instrumental in bringing people to Christ.

8. Palamas’ last years were marked by an intriguing episode. During a voyage to Constantinople, the ship he was in fell into the hands of Turkish pirates. He was obliged to spend a year in detention at the Ottoman court where he was well treated. Judging by his letters, the Turks were unusually tolerant of Christians who lived under their rule and Christian captives. Palamas was very interested in Islam and had several friendly arguments about faith with a son of Emir Orhan. Based on the remaining sources, we can conclude that in spite of his traditional allegiance to the Roman Empire, Gregory drew a distinct line between the mission of the Church and the political interests of Byzantium.

9. Palamas died on November 27, 1359 in Thessalonica. He was canonized nine years later by Patriarch Philotheos, his disciple and friend. Saint Gregory Palamas is second only to the Great Martyr Demetrius of Thessalonica in terms of popular veneration in Thessalonica. The Church of Greece canonized all family members of this great champion of hesychasm in 2009, namely his parents Constantine and Kalloni, and his siblings (Theodosios, Makarios, Epicharis, and Theodoti).