Sin

I think we Orthodox don’t talk enough about sin. Really – how many of our people actually go to Confession? And when we do speak of morality, we seem to focus mostly on sex. Our hierarchs often (and properly) criticize disordered sexuality and its effects: adultery, gay marriage, abortion and the like. As a priest, I have often warned people against watching trash on television and pornography on the internet. I’ve warned our men against imitating the disgusting sexual misbehavior of far too many politicians, entertainers, business leaders and clergy. But I wonder if we have left the misimpression that the only sins worth worrying about are sexual ones. I mean, when is the last time you heard a good sermon or read a pastoral letter on the evils of greed or gluttony?

However, the Church has traditionally condemned many sins, of which lust is only one, and there are other kinds of lust besides sexual lust. I’d put a picture of lust here, too, but you probably wouldn’t want to see it. Or would you?

When we Orthodox do talk about morality, we usually tend to accentuate the positive, trying to inspire people towards loftier goals, the great Christian virtues. We don’t browbeat people and play on their guilt. This is good. However, I think it may also be instructive and useful to approach the subject from the negative side, about the sins we need to avoid.

So here comes a new occasional series on the Seven Deadly Sins.

We’ll begin with some definitions. Someone described a philosopher as “a person who walks around telling people to define their terms”. But really, this is necessary if we’re to understand what we’re talking about here. If you’ve been reading this blog regularly, you know that what follows is one of my “hobby horses” – but it is hard for us Westerners to keep this straight. So, class, now please pay close attention.

ἁμαρτία

In the New Testament, the word “amartia” (ἁμαρτία), which we translate into English as “sin”, literally means “missing the mark”. “Sin” in the New Testament is a sports term – an archery term, where the mark is the bullseye. Today we might describe sin using a basketball term with the basket as the mark. The moral bullseye or basket is love – “love God with all your heart and mind and soul and strength”, and “love your neighbor as yourself”. (That’s far harder than a 3-pointer.) Anything which hinders us from that perfect love is what we mean by sin.

“Amartia” has no necessary connotation of personal culpability or guilt. Of course, a person who intentionally aims wrong is culpable, but in the Church’s view, most people who commit sin are not guilty. They have really tried to do good. The Protestant theology I grew up with told me that most people are fundamentally rotten. When I got into parish life I found that was just not true. Usually people miss the mark simply because we need more training or practice. And my understanding of eternal life is this: If we really want to hit the mark perfectly, God will give us all the time and help we need, in this world and the next, to keep practicing till we get it right.

I wish we could get rid of the English word “sin”. To be replaced by what? I don’t know. But in our Western legalistic Christian tradition (both Roman Catholic and classical Protestant), “sin” became a “law-court” term with overtones of culpable wrongdoing. In the popular mind, if we “sin” we have broken God’s law and are automatically guilty and deserve punishment. So God says, “Into jail, sinner. Go to hell, sinner!” Then the point of our religion becomes finding someone or Someone who will pay the price to the Judge, so we can get sprung out of God’s “slammer”. No wonder many modern folks in our culture have rejected God and Christianity and the whole concept of sin.

No! That is not at all what the New Testament or the Church Fathers or the Orthodox Church teach about sin. This is something the medieval Western legal mind read into the New Testament. God condemns no one to hell. It’s something we choose. C.S. Lewis, an Anglican who got this straight, wrote that in the End there will be 2 possibilities: Either we will say to God “Your will be done”, or God will say to us “Your will be done.” If we haven’t chosen him, he won’t force himself upon us. It’s our choice, not God’s. We Orthodox believe the key to our salvation is to grow up spiritually, get healthy. Christ our God came and gave us his Church: his Family in which we together with our brothers and sisters can achieve maturity, his School in which we can learn right from wrong, his Hospital where we can become spiritually healthy.

Would you like to get Scriptural about this? “God sent his Son into the world not to condemn the world, but that the world through him might be saved.” John 3:17

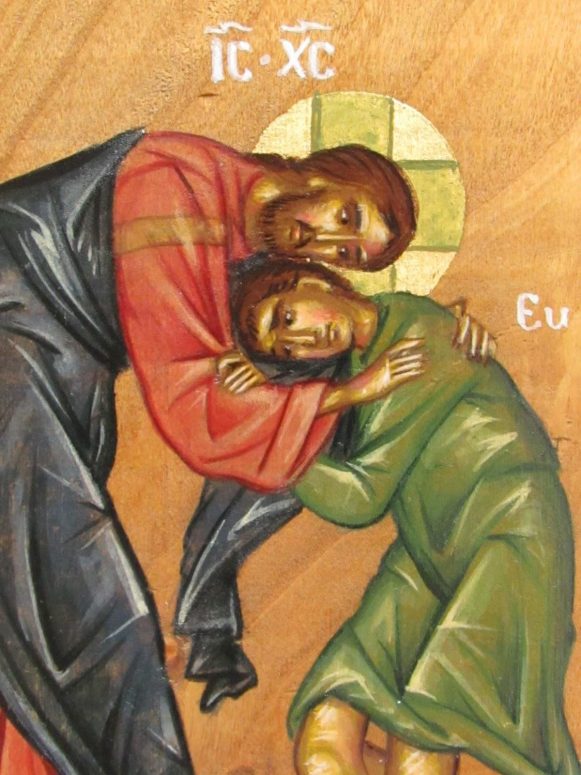

Forgiveness

Furthermore, the New Testament word which we translate as “forgiveness (“aphiemi”, ἀφίημι) usually means simply to “send” or “take” something away. (The Fathers rarely understood this to mean a legal decree of innocence.) So, to get this into English, we have to use an awkward double negative: To “forgive sin” is to “take away” our “missing the mark”. That is, the point of God’s forgiveness is not to get us off the hook legally, but to welcome us home again – like the father of the Prodigal Son – and so help get us back on the mark again.

So as we go through this series, you ex-Protestants (like me) and ex-Roman Catholics, please please try to root the Western legalistic understanding of sin and forgiveness out of your mind, and keep it out. (This will not come easily. After almost 30 years Orthodox, I’m still working on it.) But otherwise you’ll misunderstand much of what follows. Indeed, you’ll misunderstand much of what the Holy Scriptures and the Fathers and the Orthodox Church – and Jesus Christ! – are all about.

Deadly Sin

The reason we examine our sins is not so we will wallow in guilt, but rather so we can see the particular ways in which we need to get back on the mark.

This is absolutely vital because sin is dangerous, deadly dangerous. Sin is spiritual disease which, left untreated, will destroy our inner spirit and our conscience and ultimately kill our soul. We all know exactly how this works. When we first fall into a particular sin we feel bad about it, but (I’m sure you’ve noticed) if we keep it up and it becomes a habit, it doesn’t bother us so much any more, and eventually we notice it scarcely at all. Our conscience begins to go numb. Serial killers started out just like you and me, but as they proceeded to knock people off, progressively their consciences went dead, and eventually murdering no longer troubled them.

And that’s how, if we’re not careful, any sin little by little can take over and allow us to do dreadful things without a pang of conscience. We just don’t care anymore. Love dies. Obedience to God dies. And then in the end the eternal life which was given us in Baptism dies. For God is the Source of life, and if we get cut off from him – from the love of God and the love of people whom he loves – then when our bodies die, we have nothing left to take into the Kingdom. And so we wind up somewhere else. That is why we often refer to these as Seven Deadly Sins.

The little Pocket Prayer Book of my Antiochian Archdiocese, which I’m going to use as a guide through this series, titles these the “Seven Grievous Sins” (p. 28), because they “grieve God’s Holy Spirit”. Ephesians 4:30. But I like the term “Deadly Sins” better, because it’s scarier.

End of Part I