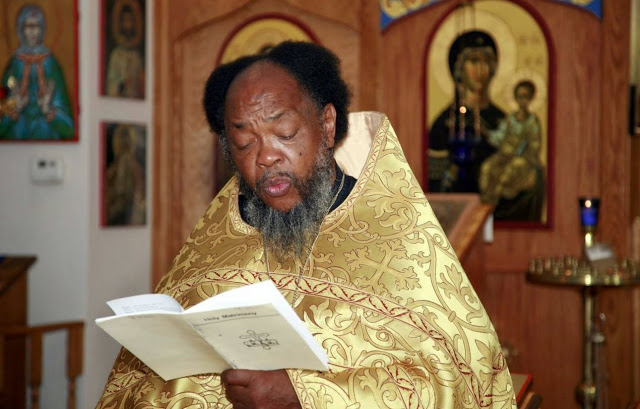

You wouldn’t suspect that the jovial Orthodox priest who carries the gold chalise with such reverence from behind the iconostasis of “Mother of Unexpected Joy” church was once a drug dealing, rambling hippie and coffee-house owner with his own underground band, not to mention an illegitimate descendent of Nathaniel Boone, the son of the legendary American hero Daniel Boone. Father Moses Berry, who is by now in his 60s, is still a rolling ball of fire, overflowing with spontaneous exuberance. He bounces from one story to another as he moves from one section of the Ozarks Afro-American Heritage Museum he founded in his native town of Ash Grove. He is a man who unravels a ball of tightly-wound stories, one knotted to another and yet another.

Father Berry’s story, in fact his entire existence, is rooted in the dark history of American slavery. The three-room museum he opened is jam-packed with heirlooms, objects and artifacts culled entirely from his family’s possession. Two faded sepia prints in oval frame reveal pictures of his great-grandmother, Maria Boone, mistress to Nathaniel, and her daughter, Caroline Boone Berry, his grandmother. They are wearing stiff, laced-up dresses with matching bonnets fashionable for ladies in the 19th century. He says that the child of a slave mistress is born between the dark and the daylight, raised in the shadowland, not of this world. They are children whose existence is denied, whose marked absence in the American consciousness is a mark of their presence.

A collage of black-and-white photos, yellowed historical documents, tools, and everyday objects align the walls of Father Berry’s personal museum revealing how the intimate personal facts of a family’s life create the historical impersonal account in a textbook. He points to a faded photo of a young Black girl in a white dress. “This is Fanny Murray at age 13 in 1866,” Berry explains. “Fanny saved a young man’s life just by doing his laundry for 10 cents a week. This is why every little thing you do is important. A simple act of loving kindness, a seemingly insignificant gesture can have an incredible impact.” The young man, who had gotten in trouble and whose family had consequently disowned him, eventually became a history professor. Underneath is another photo, color this time, of an old woman in a pink dress and a wide, flamboyant Sunday hat. “This is Ms. Olivia Murray, Fanny’s daughter, who died at 93 in 1991. She would walk down these streets in long dresses with a bonnet even after the 60s. She was an Aunt Jemmima figure and quite an embarrassment to the young people in the town. ‘Check her out,’ they would point and stare, but I would tell them you can’t dismiss people at a glance. We don’t know who the person is, who s/he really is.”

Through the personalized tour of his family’s history, Father Berry spins his own story.

Over forty years ago, an African-American teenager, Karl, leaves home at 15 after hearing that in California young people were shooting flowers instead of bullets. “California, man,” he recalls in his black rassa, blacker than his glistening skin in the hot May sun, “Once I heard about California, about flower power, and how people were living together in love, I had to go.” He hitched his way west from his native town of Ash Grove, Mo. In California, he lived in a commune, learned how to roll hashish, and to tie-dye t-shirts. He returned to his native state of Missouri where he settled in Columbia, Mo. There he “hustled” by selling leather goods, Latigo of London in particular, out of a small store front on the corner of 8th Street and Broadway, “The Strow Away.” At night he jammed jazz rock with his group “Honey Chile,” which even had a hit single in the area. He was active in the Stony Brook commune that convened by a creek in the granite hills of the area. His fortune changed when he opened an underground coffee shop, the Rainbow Bread Company. While it fronted as a “coffee shop,” as was the case with most coffee shops of the period, it made a bigger profit selling hashish and marijuana. It would have continued as a lucrative underground establishment had the Columbia police department not set it on fire. As it could not secure a search warrant, the police forced a raid. During that forced break in by the police, which resulted in almost total devastation of the coffee house, Karl and his partners were forcibly arrested and taken into custody.

Without representation, Karl was placed in solitary confinement. “It was a cell literally 5 feet by 3 feet by 7 feet. No windows. Just a chink where they could throw you a piece of stale bread.” Karl could not say for how long he was confined in the dark pit. But he feared the worst. Under the statutes, his sentence could stretch for up to 15 years in a penitentiary. “I had hit a low point. This was the end,” Father Berry remembers puncturing the somberness of the event with his full, guttural laugh that reaches down through his heart and soul to the bottom of his shoe soles. “I remember the day before I was supposed to get my sentence. I got down on my knees in that dark, narrow cell and prayed for the first time in my life. I prayed and called out to God as I had never done before. I said, ‘Lord, get me out of this one, and if you do, I promise to serve you.’”

The next morning Moses heard a key turn in the cell door. At first he did not want to come out. He had heard how the guards would periodically beat prisoners and then return them to their cells. Haunted by the visions of the brutal beatings the prisoners received at the hands of the guards he witnessed before he was placed in solitary confinement, he refused to exit. The guards had to drag him out into the light while they shouted, “You’ve been released! Get out!”

“He repented,” Father Berry muses. “The police officer who had pressed charges against me had repented. He had come to the precinct before midnight and dropped all charges. He must have come just about the same time as my prayer.” From that day forth, Moses Berry’s life changed completely. His soul had heard the call of the divine.

It would be several years, however, before Moses’s course led him to Orthodoxy. Upon his release, Moses traveled to New York City, where he became a teacher in Harlem. It was there where he met his wife, a liberal, Jewish teacher. “I remember walking down the streets of Harlem, arm in arm, singing Beatles’ songs. People must have thought we were crazy,” Father Berry reminisces. On a spontaneous whim they accepted an invitation of a friend to visit in Richmond, Virginia. After driving eight hours, they were prodded by this same friend who was Orthodox to visit an Orthodox chapel another two hours away. While the reluctance was strong, they did find the chapel; it was on the second floor of someone’s Colonial house. “This wasn’t a church; this was somebody’s living room,” Berry says. But upon entering, even with the makeshift choir of three or four women, never had he heard a service like this. “I heard things like ‘Rejoice, Laver purifying conscience. Rejoice, Wine-bowl over-filled with joy. Rejoice, sweet-scented Fragrance of Christ. Rejoice, Life of mystic festival.’ This was poetry. This was beauty and peace and love. There was incense. There was reverence. Nowhere had I heard liturgy like this. I became Orthodox from that point on.”

Since that time, Berry has striven to live out his promise to God. He has worked with at-risk youth, prisoners, and drug addicts. One of his many accomplishments included starting up a 7-step drug rehabilitation program in Detroit based on the principles of salvation in Orthodox theology.

His two most recent achievements include founding a museum and church in Ash Grove, MO. Father Berry and his family have returned to his roots. They moved out of a comfortable three-story Victorian house in suburban St. Louis into a 150-year old unmarked farmhouse, the same farmhouse in which his great-grandmother was born. “Most of the Blacks moved out of Ash Grove. My family stayed. When they heard I was going to open up a museum in that little town, ‘Be careful’ they told me, white people are not going to like it.” The museum, however, has been successful and has become a point of pride for the town.

The Ozark African-American museum houses a uniquely personal assortment of historical objects tied intimately to the “dark side” of the Boone family. Some are quilts his great-grandmother and grandmother collaborated on. One quilt, a 1790 piece, featured prominently in the Underground Railroad. The quilt in triangular green, brown, and yellow patterns would be draped over the porches of “safe houses” a signal that welcomed entry for runaway slaves. Over the doorway to the second room is a “two-lady saw,” another object the two women would use. It is smaller, thinner, and shorter, at least by a foot, than a regular saw.

Among the other objects on display is a minted coin commemorating the lynching of three Black men on Good Friday 1906 in the Ozarks and an authentic 1858 AG Brock slave tag that was used during slave auctions at the houses of that company around the South. Father demonstrates a “screw lock” which looks like a menacing wrought-iron horseshoe with a long screw transversing it at the edge of which a bolt slowly tightens over a slave’s ankles. According to Berry, it is the origin of our slang expression for “screw” as slaves would report among themselves “so-and-so got screwed.” A leather-bound, yellowing volume of The Remarkable Advancement of the Afro-American by Lancaster Water, 1898 edition, and behind that, in a glass case, the same title but the original binding from 1852. The painting and photos in the museum tell the stories of slaves who fought in the Union army and were later freed for their service, of 12-year-old runaways who were frozen to death, married couples who started churches, of rebel slaves who saw visions and organized services in the forest eventually founding the African Methodist Episcopalian church.

Another curiosity is the hand-crocheted African Mammy doll, a caricature of the Caribbean slave trade figure. The doll stands alone on a green draped coffee table at the exit of the museum. Hand-made with double lacing, the doll’s woolen face exaggerates lips nose and eyes. She is wearing a green and yellow headdress from under which protrudes black woolen cornrows. “Mammie is a West African matriarch,” Father Berry explains the subtle shadings of cultural history in everyday objects as he turns the doll upside down. “She is a Josephine Baker fruit dancer underneath,” he says as the doll transforms into a bare-bellied, buxomous exotic dancer bearing the typical platter of bananas and pineapples on her head. The doll provides a casual metaphor for the transformation of a people, a subtle symbolism for the complexities of the soul at its surface and at its depths.

Father Berry ends with one final story that underlines the importance of relationship, the one thing that can transcend the impersonality of history, the division of race, the misunderstanding of class. Several yards from the Berry-Boone farmhouse is the family cemetery. Gray stones mark the resting place of slaves who never reached their final destination on the Underground Railroad. One of Harriet Tubman’s porters is there. So are the graves of Maria Boone and Caroline Boone Berry. “It was maybe three months after we had moved into the farmhouse, so things were still messy. I drive back from the church and all of a sudden, I see this red Corvette with California plates parked by the gate blocking the way to the cemetery. I see these three blonde kids in the back. ‘What are you doing here?’ I ask them. ‘Well, I’m sorry,’ they say all polite and all. ‘We didn’t know anyone lived here.’ (He puts on a high-pitched voice mimicking all too many “white boys”). Now, I call back to them all gruff and all, ‘I am here to tell you I live here, and you are on my property. What are you doing here?’ It turns out these kids had been raised by a Black nanny who was buried in this field. ‘Mammie raised us from when we were seven years old when our own mother died,’ they said. So, these kids had been coming to her grave every year on the anniversary of her death to put flowers on her grave.’” He ends his story like a sermon. “A simple act of kindness can reach into eternity; it can save your soul besides another’s.”

“Orthodoxy is the truth. It is the one true path to salvation,” Father Berry confesses. “Once you understand what it is all about, there is no hiding from the truth.” Once Orthodox, he confesses the greatest challenge for staying Orthodox is hopelessness. “The hardest thing to do in Orthodoxy is to learn how to have hope.”

Father Moses Berry now serves hope from a golden chalise every Sunday at 10 a.m. in a small, white and red barn church with a golden onion dome in the middle of a cornfield in rural Missouri. “There is no other hope than in our Lord, God and Savior Jesus Christ,” he smiles. “I am a living example of the immanent love of God for His children, even those who have gone far astray, of despair turning into hope. We must never lose hope.”