There was a time in Russia when the most valued dowry for newly-weds was not considered to be expensive utensils, dresses or ornaments, but spiritual books. People knew: wherever faith is, there is God’s blessing on the family and everything else will come in due course. The Gospel, the Philokalia and the teachings of the holy fathers were handed down from generation to generation. But it was the Menology which had a special place among the best known sources of wisdom and goodness.

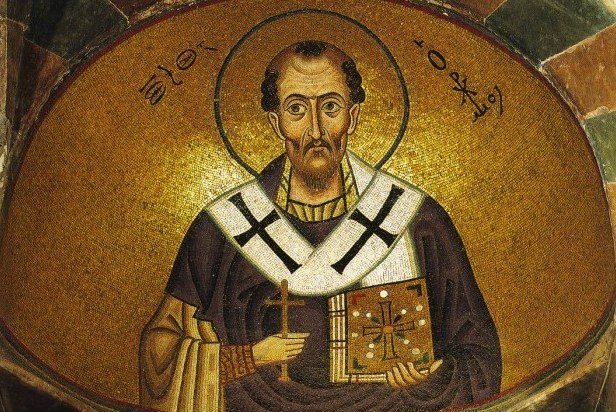

Nowadays some people do not even know what it is: It is a whole set of saints’ lives (biographies) which embraces the full yearly cycle of feast days. The Menology (Lives of the Saints) were read in the family circle and were the favourite reading matter among literate families. Not everybody knows who made the Lives of the Saints into the foundation of home libraries – not everybody knows about the wonderful pastor and distinguished spiritual writer St Dimitry of Rostov, commemorated by the Church on 10 November.

‘I have no possessions, except for holy books’

…The sun was going down in the west. That autumn day in 1709 had been a difficult one for Metropolitan Dimitry. For three days already Vladyka had been feeling weak but he had been unable to resist celebrating at the altar on the day of his heavenly patron, the Holy Great Martyr Dimitry of Salonica.

And although each step was difficult for him, he had celebrated the Liturgy particularly solemnly and joyfully, as if sensing that he was offering the bloodless sacrifice to God for the last time. A great many guests had come to congratulate him and, as usual, he was ‘not as one who ruled, but as one who served’. That day one of the nuns who had come fell ill and, forgetting his own infirmity, the Metropolitan had hurried to her to support and encourage her – only with difficulty had he returned to his cell.

It was already late when the Metropolitan had unexpectedly summoned the choir members to his side and listened for a long time to his favourite spiritual hymns and songs, leaning his aching back against the stove in order to try and relieve his fits of coughing. He thanked everyone particularly warmly and sympathetically. Keeping one of the singers back for a short while, he bowed deeply to him, thanking him from his heart for his labours (that one had helped him copy out his spiritual works).

And in

the morning the news went round all Rostov – Metropolitan Dimitry had passed

on. The bells had only just started ringing for Matins when he was found on his

knees, as if praying in front of the icons; his soul had left for the Lord.

the morning the news went round all Rostov – Metropolitan Dimitry had passed

on. The bells had only just started ringing for Matins when he was found on his

knees, as if praying in front of the icons; his soul had left for the Lord.

A great multitude of people saw Vladyka off on his last journey. The widow of Tsar Ivan Alekseevich, the Tsarina Paraskeva, came with her daughters from Moscow; laypeople and clergy flocked to bow down for the last time in front of him who had spread his knowledge throughout Russia. The poor and the beggars who for years had been clothed and fed by the Metropolitan, who had accepted them like brothers, streamed in continuously. The seminarians huddled together, as though they had been orphaned.

For many years the Bishop of Rostov had maintained a seminary in the town, using the income provided for his episcopal apartments, spending that which he could have used for himself on supporting the students, especially those from poor families. Everyone’s first thought and first feeling was, ‘We have lost him’, and only when the singing and words of the panikhida had fallen silent, did they understand and realize that ‘we have acquired him’: He had been called from his earthly labours to new labours – as an intercessor for Russia.

He had never been seen idle. He ran Church affairs and was always writing – spiritual works, instructions for laypeople and clergy – he cared for the needy and converted schismatics and heretics who had gone astray back to the truth, pained for them as for those who were perishing.

In all this there was simply no room for anything ‘private’ or ‘personal’. He had not saved any earthly wealth during his long years of Episcopal service – he had given absolutely everything away, spending it on people. His monastic poverty had reached such a point that in one letter he asked someone forgiveness because he had no way of seeing him: ‘I have neither horse, nor rider, nor sheep’.

In his spiritual testament, written not long before his repose, Metropolitan Dimitry spoke of his material situation even more openly, so that in case of his sudden death no-one would trouble themselves seeking out any earthly ‘possessions’.

‘Since I was tonsured at the age of eighteen in the monastery in Kiev, I vowed to God to live in voluntary poverty…I have not had any possessions or been attached to anything, except for holy books, I have not amassed silver or gold, I have not permitted myself any unnecessary clothing, or anything else except for essentials…Let no-one show an excess of zeal after my death and search for anything I have kept in my cell…I believe that it would be more acceptable to God that a tiny coin should remain after me than a rich inheritance which would have to be distributed’.

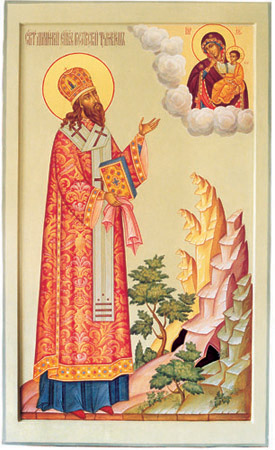

In such conditions of voluntary poverty, Metropolitan Dimitry left as his legacy for whole generations to come a great spiritual treasury – 12 volumes of the Lives of the Saints.

In such conditions of voluntary poverty, Metropolitan Dimitry left as his legacy for whole generations to come a great spiritual treasury – 12 volumes of the Lives of the Saints.42 years after his funeral, on 21 September 1732, they found his holy relics incorrupt and they started to work miracles of healing. The Holy Synod canonized St Dimitry as a newly-revealed wonderworker of Russia.

The following year the Empress Elizabeth arranged for a silver shrine to contain his relics. In 1763 the Empress Catherine walked from Moscow to Rostov to venerate his relics and transferred them into a shrine which had been prepared, carrying it herself together with bishops, as they solemnly processed around the church.

A Disciple’s Gift

Metropolitan Dimitry had been preparing for his main work since his youth. Not everyone is granted the gift that was the mainstay of his character – a constant demand to study.

He was born near Kiev to the very ordinary but pious family of a Cossack lieutenant. Having learned to read and write, as a youth he had already reached the firm decision to enter the seminary attached to the Church of the Theophany in Kiev.

His abilities and desire to study were such that although his means were modest, he was top of the class. It was then that a spark of ardent love for God flared up in his heart and his soul came to desire only one thing – to give himself over to the wholehearted service of God.

At the age of 21 he was tonsured a full monk and at 25 he had already been ordained a hieromonk, that is, a priest-monk. At that time, as before, he did not stop reading, entering into the details of every question to do with Church history, especially controversial questions, so that as a pastor he would be able to give only correct answers to the uneducated. Times were not easy then: in the southern Russian lands the true confession of Orthodoxy had to be defended against the advance of Western preachers.

The young priest was appreciated for his zeal and pastoral responsibility. Not ten years had passed since his studies and Kiev, Chernigov, Slutsk and Vilno were already competing with one another to get the young pastor to come to them, as he used his constant teaching for the good of the Church. Early on he was made an abbot and took on responsibilities for a monastery. Some were astounded, but the bishop who had appointed him foresaw a still higher calling for him and hoped for a mitr-e for one who was named Di-mitr -y, that is, he saw in him a future bishop.

His acceptance of the position as an abbot was not an honour for him. It was a call to still more zealous service. Soon Abbot Dimitry moved to the Kiev Caves Laura in order to pursue his learned studies. 1684 marked for him the start of a twenty-year period of labour connected with the compilation of the many volumes of the Lives of the Saints. This turned into the main work in his life, which he continued in his monk’s cell, as a rector and later, when Patriarch Adrian in Moscow transferred him to Rostov, as an archpastor. Many years of labour were required so that even today people in Russia can simply stretch out an arm and take down the volume they need and read a chapter about one or another saint, starting from the first centuries of Christian history.

To bring the saints close to us

In order to understand what the main service of St Dimitry of Rostov is, we have to present something of the history of Russian spiritual literature. Up until him the Lives of the Saints of Metropolitan Macarius of Moscow were generally used in church. They were less complete and, above all, they were written in Church Slavonic and used an old-fashioned vocabulary.

This is why Metropolitan Peter of Kiev, who blessed Abbot Dimitry’s labour to compile new Lives of the Saints, wanted them to be written in such a way that they could be read not only by clergy but also by laypeople.

In order to add to what was already known about the saints, St Dimitry used a great many new sources: Russian prologues and sayings of the fathers, also Greek books which he obtained from Mt Athos (especially the works of St Symeon Metaphrastes who had done a great deal of work on saints’ lives in the tenth century).

St Dimitry tried to write in the same way as a good iconographer paints icons: so that the face or spiritual image of the saint would be visible. The facts he collected were of interest; thanks to his books and their accessible language what had once been little known rose up from his pages as living, apostles full of the spirit, great hierarchs of the Church, martyrs who glorified God through the strength of their faith, venerable confessors who imitated Christ in their lives, the humble righteous and fearless prophets.

‘A spiritual rainbow’ has risen over the earth which was full of evil. Is it possible to be despondent, when we have such friends and intercessors, do we need to sorrow for what we have lost when there, with God, there are many who are dear to us and are waiting for us, they know us and take part in our lives through their prayers, sometimes even when we do not ask them to help us?!

St Dimitry was able to convey to his readers the sense that the saints are close, which he more than once experienced himself. On a number of occasions during his work those of whom he was writing appeared to him in his sleep, as if to assure him that the Church in Heaven was praying that his work would be successfully completed for the benefit of the Church on earth.

Many well-known spiritual instructors say: when you read the life of this or that saint, know that he stands alongside you. The Lives of Saints by St Dimitry of Rostov were read in every corner of Russia. We know that they were the constant reading of the family of the last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas Alexandrovich Romanov.

What do we choose?

Unfortunately, nowadays one of the prophecies of the holy fathers is coming true. This is that the time will come when ‘the crumbs that the forebears gathered up will be left lying on the shelves by their descendants. There are not many families today who have even one or two volumes of the Lives of St Dimitry of Rostov in their home library. That which our ancestors prized is disappearing from our cultural heritage and the historical memory of the people, together with traditional concepts of humanity, goodness and truth.

Twenty years have passed since churches were opened again in Russia and we have had the opportunity to choose what we nourish our souls and minds with. The choice is between what is indirectly and apparently easily transmitted on screens and what demands a certain violence against ourselves: what we have to search out to acquire, what cannot be found amid the piles of everyday books, but which Orthodox Christians at one time could not even conceive of living without. The first choice is easier, the only question is – does it often leave any deeply-rooted green shoots? The second choice is incomparably harder, but it constitutes the first step towards spiritual freedom, which goes hand in hand with responsibility.

Some people are troubled by the seriousness of spiritual literature. Of course, here the subject may not be so captivating, there is not the usual humour; this is a different sort of reading matter. But perhaps those who today face this choice will find the simple accompanying words of St Dimitry of Rostov helpful: ‘The righteous has no sorrow which cannot be changed into joy, just as the sinner has no joy which cannot be changed into sorrow’. In reality, what is solid and precious is only that which has been obtained through effort and confirmed by experience.