The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament proclaims [H]is handiwork. Day pours out the word to day, and night to night imparts knowledge (Psalm 18: 1–2).

Both the Fathers of the Church and modern behavioral scientists have long inquired into the psycho-spiritual process of knowing. Both sources suggest the strong effects that images and our interaction with the natural world have on this process. Through experiencing the important role of icons in prayer and everyday life, the Orthodox Christian gains a practical understanding of the relation between the body, soul, and spirit and how sense perception can help or hurt us in our journey to perceive God’s living presence.

Perception and the makeup of the creature

The focal point is the spirit

God created mankind of not only body, but also soul and spirit . Consider the spiritual meaning of God’s creation of mankind as recounted by the writer of Genesis (2:7): “…then the Lord God formed man of dust from the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being.” We can consider that the word ‘spirit’ as describing the soul. As Solomon, the son of King David and the writer of Ecclesiastes writes (12:7): “…the spirit returns to God who gave it.” The prophet Zechariah, almost 500 years later, during the time when the Jews were under the captivity of the Persians in Babylon, said: “Thus says the Lord, who stretched out the heavens and founded the earth and formed the spirit of man within him.” (12:1). St. Paul tells the Corinthians “If there is a physical body, there is also a spiritual body” (1Cor 15:44).

The implications of man being made as body and soul-spirit were not lost on the Fathers of the Church. They recognized the differences in knowing or perception between these elements of the creature person. Significantly, the Fathers distinguish between sensation and reason, which come from the body, and spiritual knowledge or perception, which come from the soul and leads us to God. Ilias the Presbyter tells us: “…sense perception is involved with practical and material realities…” (Philokalia III). St. Gregory Palamas (Philokalia IV) notes: “since this faculty [sense perception] is united to our reason we have invented multifarious arts, sciences and forms of knowledge.”

Knowing with the mind-body

Modern science has expanded our understanding of the physical body-mind knowing process (Morelli, 2006). Psychologists readily make a distinction between sensation and perception. Weiten (2007) notes: “Sensation involves the stimulation of sense organs, whereas perception involves [the] selection, organization and] interpretation of sensory input.” The scientific observation underscores how God gives us neuro-physiological processes that underlie sensation and perception as the way we know and understand His created world. As discussed below, by understanding how these processes function, we can better appreciate how mental-physical knowing either facilitates or hinders spiritual knowledge or spiritual reason.

Capacity of working consciousness

One important discovery made by research psychologists is that the average individual has seven slots, plus or minus two, in which to store information at any one time. The initial study conducted some years ago by George Miller (1956) had the whimsical title: The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity to Process Information.i When the capacity of working consciousness is filled, new information is either not stored or replaces the information currently in store. Applying these findings to prayer and spiritual perception, ideally one’s working consciousness is focused on that which is Godly. Sensory distractions, however, can interfere and replace centering on the Divine with centering on what makes up the natural world.

Ilias the Presbyter points out, “When the intellect has been drawn down from the realm above [God] it will not return thither unless it is completely detached from worldly things through concentration on things divine” (Philokalia III). St. Diadochos of Photiki indicates: “While the intellect tries to think continually of what is good, it suddenly recollects what is bad, since from the time of Adam’s disobedience man’s power of thinking has been split into two modes (Philokalia I).

St. Anthony the Great tells us: “Man is attacked by his senses through the soul’s passions. The bodily senses are five: sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch. Through these five senses the unhappy soul is taken captive when it succumbs to its four passions…self-esteem [narcissism], levity, anger and cowardice” (Philokalia I). Based on this teaching, those striving for spiritual knowledge work at focusing on the things of God so that we choose as much as possible that what passes through our senses is Godly. St. Anthony tells us: “the eye perceives the visible; the intellect apprehends the invisible” (Philokalia I).

Icons: An aid or hindrance to spiritual perception?

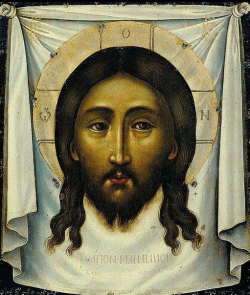

True icons that aid spiritual perception: Focusing on the kingdom of God

In the Orthodox Church icons are considered windows or doors to heaven, rather than an opportunity to contemplate nature. The ethos of the icon can be captured by the first verse of the prayer before the Cherubimic Hymn said during the Holy Saturday Vesperal Divine Liturgy: “Let all mortal flesh keep silence and in fear and trembling stand pondering nothing earthly minded.” The perception engendered by icons must be of the spirit, not what can be perceived by the body or what is of nature. In this sense, icons can enhance spiritual perception and point us to the kingdom of God.

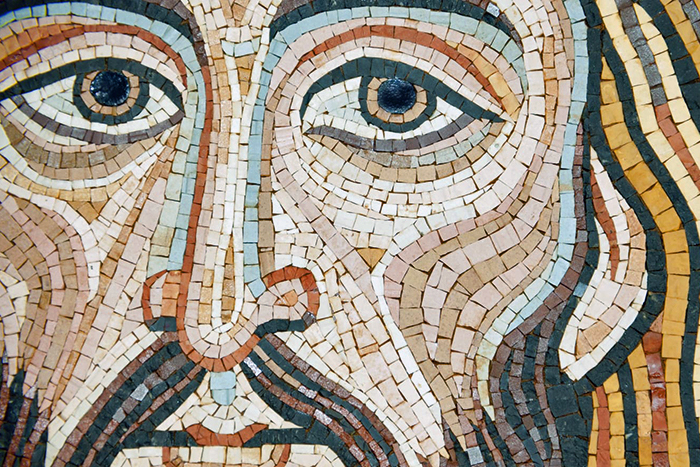

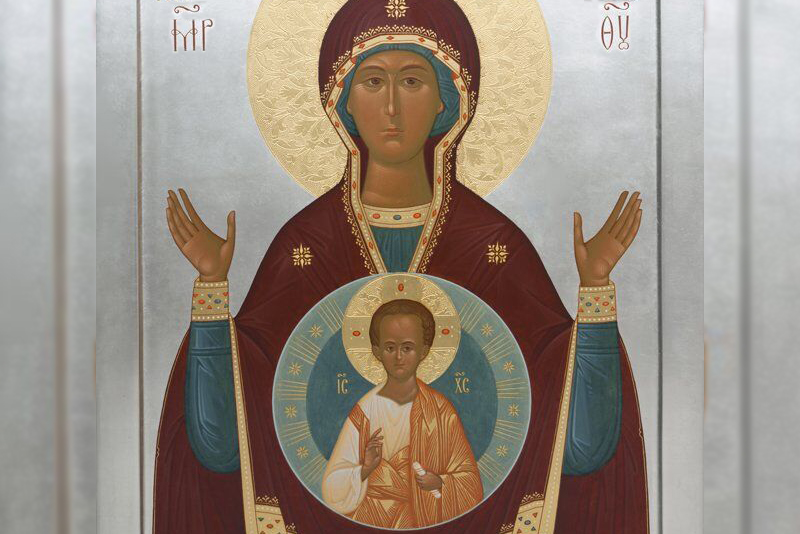

For example, consider the following two examples of Byzantine icons:

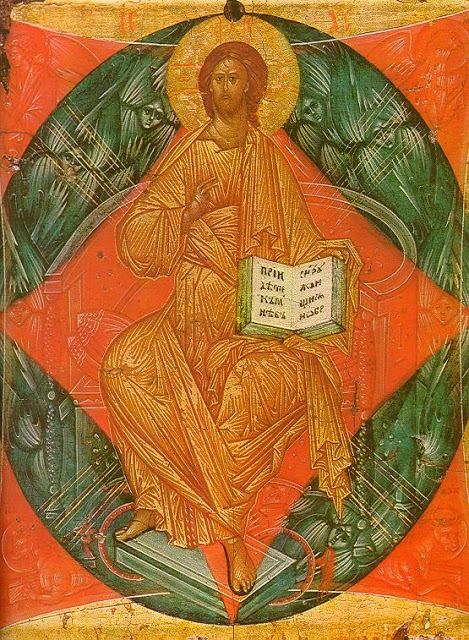

We can also consider a Byzantine icon of a much later period which can aid us in contemplating the transcendence and power of the Godhead:

When gazing at the Trypitich of the Passion (below), who cannot share in the sorrow of the Theotokos and the Beloved Disciple and cry out in their hearts as they sing at Great Vespers on Holy Friday: “Glory to thy condescension, O Lover of mankind?”

Cultivating spiritual perception

Evdokimov (1998) cites Our Lord’s words: “I tell you the truth, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Mt 18:3), explaining that these words were taken literally by the Desert Fathers. He reminds us of the instruction given to us by St. Isaac of Syria (Seventh century AD): “When you prostrate yourself before God in prayer, become in your own judgment like an ant, a worm, or a beetle. Do not speak before God as a man who knows anything, but stammer and approach [H]im with a childlike spirit.” Evdokimov interprets this as follows: “[w]e must read the desert Fathers iconographically, just as we might contemplate an icon.”

Iconographer and theologian Leonid Ouspensky (1978) describes the intent of the iconographer in rendering a less-than-realistic model: “The unusual details of appearance which we see in the icon—in particular in the sense organs: the eyes without brilliance, the ears which are sometimes strangely shaped—-are emphasized in a non-naturalistic manner, not because the iconographer is unable to do otherwise, but because their natural state is not what he wants to represent” [emphasis added].

The theologian goes on to explain: “The icon’s role is not to bring us closer to what we see in nature, but to show us a perception of the spiritual world…This non-naturalistic manner of representing in the icon the organs of sense conveys the deafness, the absence of reaction to the business of the world, impassiveness, detachment from all excitement and, conversely, the acceptance of the spiritual world by those who have reached holiness.”

False icons: Paintings focusing on nature

Now let us consider what Ouspensky refers to as the pseudo-icon period, that is, the paintings that infiltrated the Eastern Church during the Western Church incursion which started under the reign of Tsar Peter I (1689–1725 AD). How could this happen? Peter I started a cultural revolution based on what he considered Russian backwardness compared to the more progressive West.ii Ouspensky (1992) summarizes: “The Orthodox icon was accused of being “old-ritualist,” while the humble imitation of Roman Catholicism was accepted as Orthodox and, as such, is obstinately defended even now by many members of the hierarchy and the faithful.” [emphasis mine]

Now let us consider what Ouspensky refers to as the pseudo-icon period, that is, the paintings that infiltrated the Eastern Church during the Western Church incursion which started under the reign of Tsar Peter I (1689–1725 AD). How could this happen? Peter I started a cultural revolution based on what he considered Russian backwardness compared to the more progressive West.ii Ouspensky (1992) summarizes: “The Orthodox icon was accused of being “old-ritualist,” while the humble imitation of Roman Catholicism was accepted as Orthodox and, as such, is obstinately defended even now by many members of the hierarchy and the faithful.” [emphasis mine]This Russian practice continued into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and even extended into the churches under Russian jurisdiction in the diaspora, such as in North America. The influence of this pseudo-icon trend even reached Orthodox Churches in the Holy Land, Lebanon, and Syria. Ouspensky continues: “The abrupt changes under Peter I only accelerated the process of desacralization championed by [pseudo-iconographers] Ushakov and Vladimirov…” Below are examples of such pseudo-icon paintings:

Commenting on such paintings, St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco, whom we commemorate as the Wonderworker, said of the Western influence on the Russian Church: “It also wrought horrible moral damage…[an] alien influence touch[ing] Iconography as well. Images of the Western type began to appear, perhaps beautiful from an artistic point of view, but completely lacking in sanctity, beautiful in the sense of earthly beauty, but even scandalous at times, and devoid of spirituality. Such were not Icons. They were distortions of Icons, exhibiting a lack of comprehension of what an Icon actually is.” iii

Seeing the naturalistic beauty in a face, or bodily features or even the natural world would surely distract us from the inner stillness for which our spiritual fathers tell us to strive.

Use of the focused attention of our mind to aid spiritual perception

True Byzantine icons focus us on the presence of God so that limited human working consciousness is not filled up with the elements of nature, but is now detached to be in the silence that can contemplate heavenly reality (Ouspensky, 1992). Spiritual perception may be aided by a common, normal everyday experience called dissociation, or splitting mental processing into two simultaneous streams (Hilgard 1992, Spiegel, 2003).

For example, all of us at times have been in a state of ‘focused attention,’ that is, concentrating on an object or activity to the point that we become less responsive to what is occurring around us. Our consciousness is focused on something else other than the reality of God’s presence. Evdokimov (1998) reminds us: “Familiarity with icons purifies the imagination, teaches “the fasting of the eyes” in order to contemplate beauty chastely…the image of God delights us.”

St. Diadochos of Photiki tells us: “No one, however, can come to fear God completely [with the soul purified and made malleable] unless he first transcends all worldly cares; for when the intellect reaches a state of deep stillness and detachment, then the fear of God begins…purifying it with full perception from all gross and cloddish density, and thereby bringing it to a great love for God’s goodness”iv (Philokalia I).

Research on the limited capacity of working consciousness, cited above (Miller, 1956), well explains this. If our minds are filled with non-Godlike, naturalistic elements, even on a human level, they will displace our focus on God.

The eye is the lamp of the body. So, if your eye is sound, your whole body but if your eye is not sound, your whole body will be full of darkness. If then the light in you is darkness, how great is the darkness! “No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon (Mt 6:22–24).