The Transfiguration is one of the Twelve Great Feasts of the Orthodox Church, celebrated on the 6th of August. Described in the first three Gospels (Matt 17: 1-9; Mark 9: 2-8; Luke 9: 28-36), its commemoration has become uncommon in many non-Orthodox churches, which is unfortunate as there is much to discover in this event. Being one of the Great Feasts, there is also a rich heritage of iconography surrounding the Transfiguration of Our Lord.

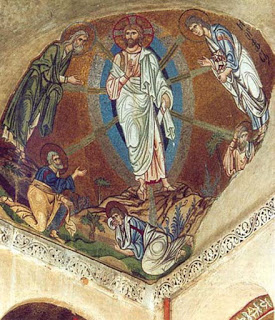

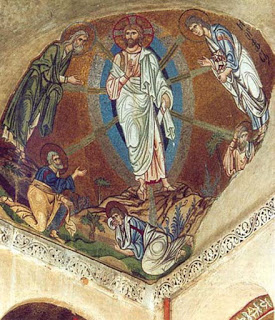

The earliest surviving image of the Transfiguration is from St Catherine’s monastery in Sinai, a place which, because of its seclusion, is home to many early icons. In the apse of the catholicon there is a mosaic of the Transfiguration, dating from the middle of the sixth century.

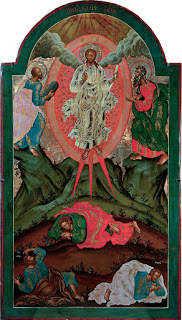

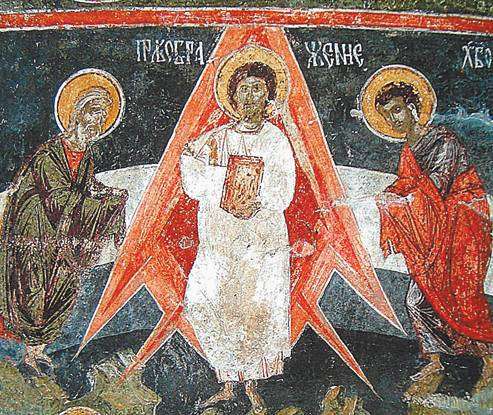

Christ is the centre and focus of the image, his hand held in a blessing, eyes directed at us. His clothes are depicted “white as light” as the Gospel writers describe, and the glory of God overshadowing the scene is shown by the mandorla around his body. From His body, shafts of light are shown striking each of the five others present: to Christ’s right, the Prophet Elijah; to His left Moses; scattered about His feet, the Apostles John, Peter, and James.

The mosaic captures the drama of the event: the three Apostles on their faces in confusion, whilst Christ stands serenely in the centre above them, flanked by Moses and Elijah, who appear to be blessing Him. All subsequent icons of the Transfiguration vary little from this basic composition.

The mountain on which the Transfiguration took place is identified by St Jerome as Mount Tabor. The mountain plays an important part in divine revelation, as described by Scriptures, and links Moses and Elijah who are miraculously present by Christ’s side. Moses ascended Mt Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments and converse with God in a great cloud of divine glory (Ex. 24:12-18; Ex. 33:11-23; 34:4-6,8). Elijah was told to ascend Mt Horeb (probably an alternative name for Sinai) where he heard the voice of God in the “gentle breeze”.

In the Biblical account as well as in icons, these two conversers with God are now shown in conversation with Christ Himself, a clear indication to Jesus’ divinity. Icons further interpret their presence, following the words of the Church Fathers, by showing Moses holding a book: representing the Torah. Elijah, in animal skins reminiscent of John the Baptist represents the prophets, while Moses represents the Law. Jesus Christ is the fulfillment of both.

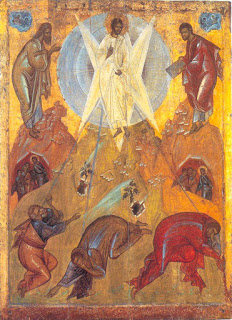

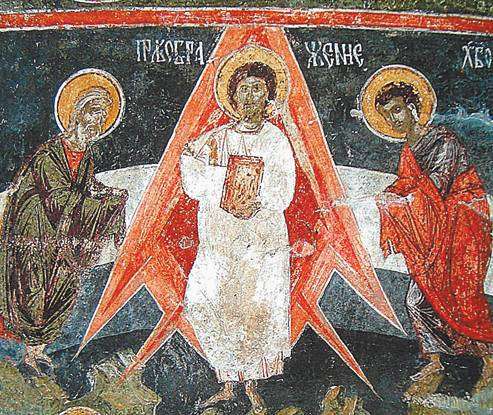

The Icon of Theophanes the Greek

Theophanes the Greek (Θεοφάνης, ca 1340 – ca 1410) was one of the greatest iconographers in Muscovite Russia, and was noted as the teacher and mentor of the great Andrei Rublev. He moved from Constantinople to Novgorod in 1370, and from there to Moscow in 1395. Theophanes was described by his contemporaries in Moscow as being “learned in philosophy,” and he was accomplished in bringing the teachings of the Holy Fathers on the Transfiguration into his own icon of the subject. The geometry of the image emphasizes the serenity of Christ compared with the ordered disarray of the Apostles: Peter reaching out a hand as though in the middle of his sentence: “Lord it is good for us to be here…” (Matt 17:4)

Theophanes’ bold icon is divided intwo: Christ and the Apostles on Mt Tabor, whilst Moses and Elijah are removed to separate, but adjacent, peaks.

Theophanes was not the first iconographer to do this: the mountains of Tabor and Sinai/Horeb are different and so it was already common to depict Moses and Elijah standing on different peaks, leaning in toward Christ. What Theophanes emphasizes though, is the distinction between the two Old Testament saints on the one hand, and the Apostles of Christ on the other. Through three beams of light, he draws the three Apostles, and us, into the dazzling light that surrounds Jesus. By doing so, Theophanes is presenting us with the already ancient teaching that the Transfiguration was not only an event for us to witness, but a process that we should ourselves partake in.

The Event and the Process of Transfiguration

We heard this voice which came from heaven when we were with Him on the holy mountain. And so we have the prophetic word confirmed, which you do well to heed as a light that shines in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts

-St Peter (2 Peter 1:10-19)

In the Gospels, the Transfiguration comes just six days after Christ’s long discourse on the the End of the World, the Last Judgment and the Second Coming of Christ. Christ finishes His words with the promise: “there are some standing here who shall not taste death till they see the Son of Man coming in His Kingdom”. The Transfiguration, then, is the realization of Jesus’ promise, and so what the Apostles experience is a foretaste of the future life – “the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ”, according to St Peter.

In Theophanes’ Icon of the Transfiguration, for perhaps the first time in an icon, the ascent and descent of Mt Tabor is shown. This is an important part of the event: Christ did not suddenly transfigure Himself amid His disciples while preaching in Galilee. Instead, Christ chose three of His disciples, He led them up the mountain “to pray”, and there they beheld the future glory of God in the present.

Yet after the ascent came the descent. No one could experience such divine glory for a sustained time in this life: it is the promise of the Future Life. What is shown in the icon is that such an experience is for all of us. The geometry of Theophanes’ icon, which draws us into the scene, does not do so that we may observe it, but as an exhortation for us to experience it too.

We too must ascend the spiritual mountain – and there are enough writings from the Desert Fathers on what this spiritual ascent consists of. And at the summit, in prayer, those shafts of divine light can penetrate us too.

In later icons, the Apostles are shown in the same “ordered disarray” of the first Sinai mosaic, but their facial expressions are changed from fearful to sleepy (see the 19th century icon below). This follows Luke’s account, where it describes the Apostles being woken from a heavy slumber to witness the Transfiguration; it is this weariness that explains their inability to understand the significance of the event, and the conversation between Christ and the Old Testament saints regarding His future Crucifixion. There too is a lesson: along with the spiritual assent, and prayer, watchfulness is needed. When Elijah heard God on Mt Horeb, it was not in the roaring wind, earthquake, or fire, but in the overwhelming silence. What could he have heard if he had been inattentive? What can we gain from God if we are inattentive?

You were transfigured on the Mount, Christ God revealing Your glory to Your disciples, insofar as they could comprehend. Illuminate us sinners also with Your everlasting light, through the intercessions of the Theotokos.

O Giver of light, glory to You.

The Transfiguration is one of the Twelve Great Feasts of the Orthodox Church, celebrated on the 6th of August. Described in the first three Gospels (Matt 17: 1-9; Mark 9: 2-8; Luke 9: 28-36), its commemoration has become uncommon in many non-Orthodox churches, which is unfortunate as there is much to discover in this event. Being one of the Great Feasts, there is also a rich heritage of iconography surrounding the Transfiguration of Our Lord.

The Transfiguration is one of the Twelve Great Feasts of the Orthodox Church, celebrated on the 6th of August. Described in the first three Gospels (Matt 17: 1-9; Mark 9: 2-8; Luke 9: 28-36), its commemoration has become uncommon in many non-Orthodox churches, which is unfortunate as there is much to discover in this event. Being one of the Great Feasts, there is also a rich heritage of iconography surrounding the Transfiguration of Our Lord. The mountain on which the Transfiguration took place is identified by St Jerome as Mount Tabor. The mountain plays an important part in divine revelation, as described by Scriptures, and links Moses and Elijah who are miraculously present by Christ’s side. Moses ascended Mt Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments and converse with God in a great cloud of divine glory (Ex. 24:12-18; Ex. 33:11-23; 34:4-6,8). Elijah was told to ascend Mt Horeb (probably an alternative name for Sinai) where he heard the voice of God in the “gentle breeze”.

The mountain on which the Transfiguration took place is identified by St Jerome as Mount Tabor. The mountain plays an important part in divine revelation, as described by Scriptures, and links Moses and Elijah who are miraculously present by Christ’s side. Moses ascended Mt Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments and converse with God in a great cloud of divine glory (Ex. 24:12-18; Ex. 33:11-23; 34:4-6,8). Elijah was told to ascend Mt Horeb (probably an alternative name for Sinai) where he heard the voice of God in the “gentle breeze”.