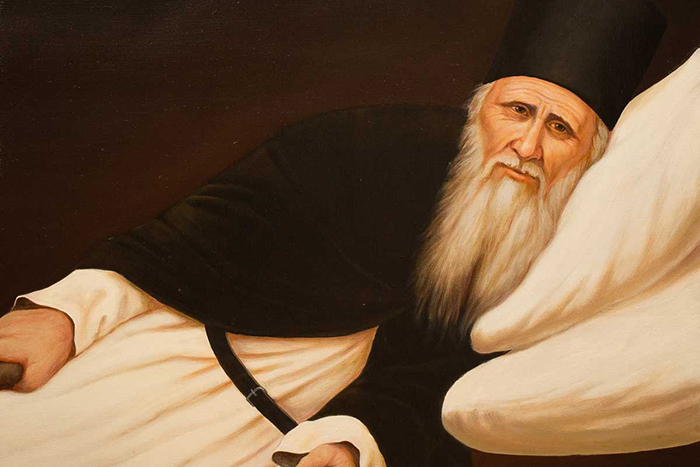

St. Alexander Nevsky (1263)—in schema Alexis—grand prince of Vladimir. Helene Iswolsky speaks of his ‘heroic valor, exemplary life, and devotion to his faith’ (Christ in Russia: The History, Tradition, & Life of the Russian Church[Milwaukee: The Bruce, 1960], p. 50). Noting that St. Alexander was an exception to the general weakness of the princes of 13th-c. Vladimir, John Fennell writes, ‘Not only was he canonized, but he was also regarded throughout Russian history as the great Russian warrior, indeed by some as the saviour of Russia…’ (A History of the Russian Church to 1448). In the Tale of the Life & Courage of the Pious & Great Prince Alexander in the Second Pskovian Chronicle, a Westerner who visited St. Alexander is said to have returned to his people telling them, ‘I went through many countries and saw many people, but I have never met such a king among kings, nor such a prince among princes’ (Serge A. Zenkovsky, ed. & trans., Medieval Russia’s Epics, Chronicles, & Tales,). Here is the account of his life in the Prologue (St. Nicholas [Velimirović], The Prologue from Ochrid, Vol. 4):

The son of Prince Yaroslav, his heart was drawn to God from his youth. He overcame the Swedes on the river Neva on July 15th, 1240, whence he took the name ‘of the Neva’ [Nevsky]. On that occasion, Ss Boris and Gleb appeared to one of Alexander’s generals and promised their aid to the great prince, their kinsman. Among the Golden Horde of the Tartars, he refused to sacrifice to idols or pass through fire. The Tartar Khan valued him for his wisdom, and his physical strength and beauty. He built many churches, and performed innumerable works of mercy. He entered into rest at the age of forty-three [having been clothed in the great schema], on November 14th, 1263 . . .

According to the Tale, St. Alexander — was taller than others and his voice reached the people as a trumpet, and his face was like the face of Joseph, whom the Egyptian Pharaoh placed as the next king after him in Egypt [Gen. 41ff]. His power was a part of the power of Samson and God gave him the wisdom of Solomon and his courage was like that of the Roman King Vespasian, who conquered the entire land of Judea. (Zenkovsky, p. 226)

Christopher Dawson has suggested, and lamented, that in the historical transition from pagan to Christian kingship in northern Europe, ‘the heroic ethos’ associated with the king was lost. Thus, he writes, ‘The royal saints of Anglo-Saxon England were, for the most part, men who were defeated in battle by the pagans, like St Oswald and St Edwin, or men who resigned their crowns to become monks, like St Sebi, of whom it was said that he ought to have been a bishop rather than king’ (p. 73). Dawson considers St. Olaf of Norway a rare ‘authentic representative of the Northern heroic tradition’ (Religion & the Rise of Western Culture [Garden City, NY: Image, 1958], p. 96). It strikes me that if Ss Boris and Gleb could be compared to the English Saints Dawson mentions, St. Alexander, like St. Olaf, is more in line with the heroic ethos, reminding one of the legendary connections of the early Russian rulers to Scandinavia.

He is certainly a champion of Orthodox Russia against the encroachments of Catholicism. Concerning St. Alexander’s battle with the ‘pseudo missionary’ Teutonic Knights, there is reproach even in the estimation of the Roman Catholic writer Helene Iswolsky:

Though not supported by the Holy See, they had been called to the Baltic by Bishop Albert and claimed to bring Christianity to the pagans by ‘sword and fire’. After completing the conquest of the seashore, they marched on the land of Russ ignoring the fact that its people had been Christian for more than one hundred fifty years, and regarding them as merely ‘schismatics’. (pp. 48-9)

Of course Iswolsky is quick to claim that in the 13th c. ‘it was not so much dogmatic conflicts, as the differences of rite and liturgical customs which the Russians and the Germans held against each other’ (p. 50). But it is a claim contradicted by an interesting story related in the Tale, a text Zenkovsky notes (p. 225) received its final form already within 20 years of the Saint’s repose:

Once there came to him the envoys of the Pope from Great Rome saying: ‘Our Pope spaketh the following: I have heard that thou art worthy and glorious and that thy land is great. Therefore I send to thee Golda and Gemond, two most wise out of my twelve cardinals, to give you the opportunity of hearing their teaching about Divine Law.’

But Prince Alexander, after consulting with his wise men, answered him, saying:

‘From Adam to the Flood;

from the Flood to the confounding of the languages;

from the confounding of the languages to the birth of Abraham;

from Abraham to the crossing of the Red Sea by the children of Israel;

from the Exodus of the sons of Israel to the death of King David;

from the beginning of the reign of Solomon to the time of Augustus, the Emperor;

from the beginning of the time of Augustus to the birth of Christ;

from the birth of Christ to the Passion and Resurrection of the Lord;

from his Resurrection to his Ascension into heaven;

from his Ascension into heaven to the reign of Constantine;

from the beginning of the reign of Constantine to the First Council;

from the First Council to the Seventh Council,

all the happenings we know well, all of this [sacred history],

and we do not accept your teaching.’

And they returned home empty-handed. (Zenkovsky, pp. 233-4)

St. Alexander must be one of the few Saints to have been the subject of a film featuring a respected director as well as a respected composer—Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky (1938), with a score by Sergei Prokofiev. I highly recommend this movie—though he seems not wholly to approve, Fr Anthony Ugolnik points out that despite being a ‘product of “socialist realism”’, in Eisenstein’s film ‘the hero is . . . invested with religious symbolism’ (The Illuminating Icon [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1989], p. 254)—but even I must admit that there is some truth to Iswolsky’s characterization of its portrayal of the Catholics as ‘crude’ (p. 49)! Of course there is also a very recent film about St. Alexander (HT Andrew Cusack)—Alexander: Battle of the Neva (2008). Judging by the trailer, it looks very exciting indeed!

Here is the apostichon in Tone 2 at Glory from Great Vespers for the Feast of the Translation of St. Alexander’s relics (Vigils of the Saints Vladimir & Alexander Nevsky [Bussy-en-Othe, France: Orthodox Monastery of the Veil of Our Lady, n.d.], p. 26):

Come all ye Russian ranks and praise ye the good chief captain; ye powers praise the wise administrator; ye soldiers the bravest of warriors; ye lovers of Orthodoxy a firm confessor ready to be a martyr. Obey your leader and submit, and having seen his end, imitate his faith.

The Troparion of the Feast in Tone 4 offers an interesting extension of the Tale’s comparison of the Holy Prince to the Righteous Joseph the All-Comely:

O Prince Alexander, thou Russian Joseph, reigning not in Egypt but in Heaven, recognize thy brethren and also receive their supplications, increasing, by thy gift for making thy land bear fruit, the corn of its people, fencing thy princely city with prayers and fighting against the adversary for thy heirs, the people who are faithful to God. (p. 26)

Furthermore, it is interesting to note the emphasis in the stichera at Lauds (in Tone 8) on St. Alexander’s greater esteem for the heavenly kingdom than for the earthly:

O most glorious wonder! He who is master of the world leaves the world. He who bears the Russian scepter lays it aside; he takes off his purple and covers himself with a burial pall; his head is crowned with a royal diadem that he puts off himself, and he leaves the temporal kingdom on this earth assured of the eternal Kingdom in Heaven where he is crowned with a royal crown. (p. 33)

I conclude with St. Nicholas’s ‘Hymn of Praise’ for St. Alexander from the Prologue, where we see the implications of the Saint’s piety—as displayed particularly in his tonsure—elabourated in an interesting way:

A knight of Christ, St. Alexander,

A prince of the people and servant of the Lord—

Ruler on earth and slave of the Almighty—

This was the life of Nevsky.

On the outside opulence, on the inside weeping;

On the outside struggle, on the inside serenity;

On the outside illusion, on the inside truth.

Christ was the prize of this hero,

Both in war and deceptive peace.

In torment, Christ was his joy,

In suffering, Christ was his assurance,

In victory, Christ was the victor,

And in death, Christ was his Resurrector!

To him, in both worlds, all was Christ!

He was the end; He was the living goal.

The pious prince was an exemplar to his people,

Of how one should serve the Lord.

O holy Prince, help us also,

By your brilliant power, by your holy prayers!