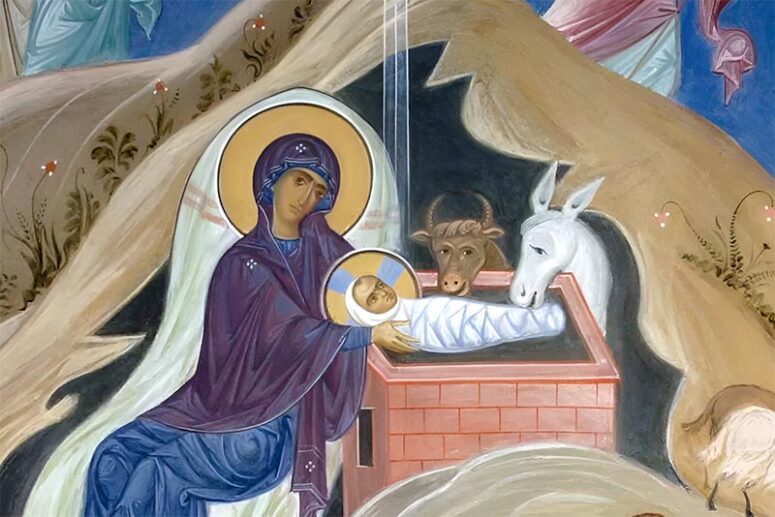

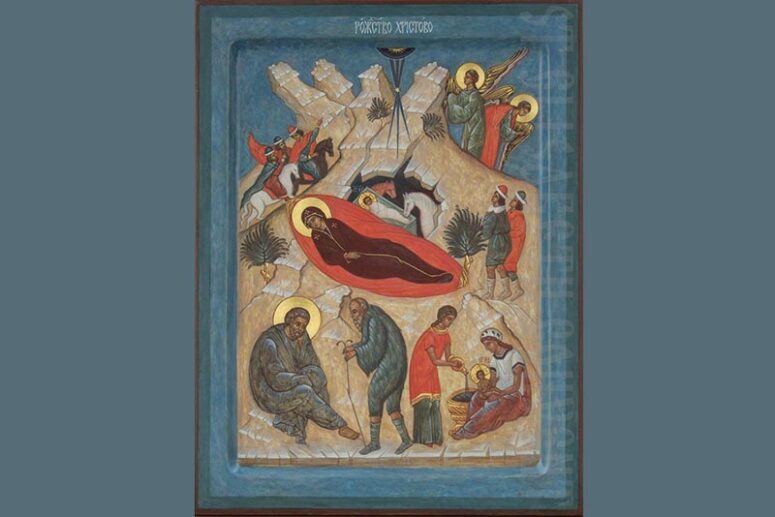

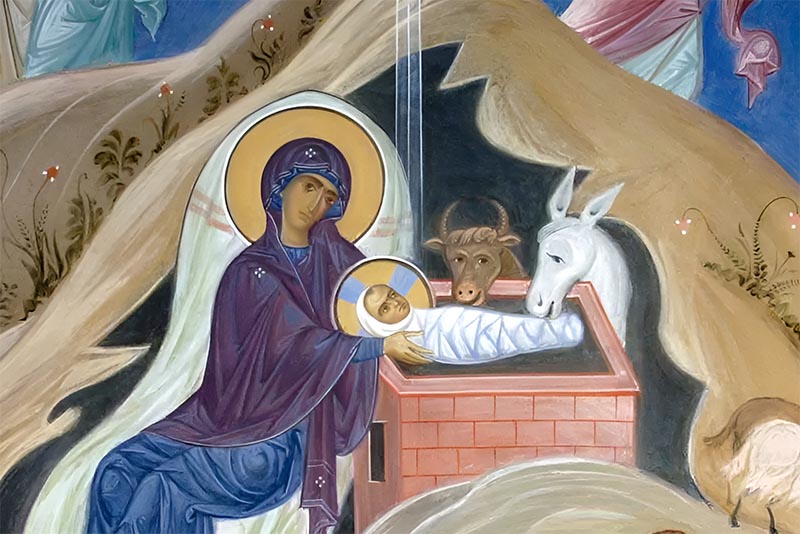

The ox, the donkey, the sheep — how did these humble creatures find their way to the manger in the cherished Nativity scene? This tableau, with its donkey, calf, and curly white lambs surrounding the Christ Child, warming Him with their breath, is both familiar and heartwarming. Yet, it’s intriguing to ponder their origins in this sacred setting.

On one hand, the creche, traditionally depicted as a cave, was likely a shelter where shepherds housed their livestock. It’s easy to imagine the animals’ surprise at finding the Divine Child nestled in their manger, an unexpected holy presence in their humble abode.

However, the New Testament itself makes no mention of animals at Christ’s birth. The inclusion of oxen, donkeys, and sheep is a product of Church tradition, with holy Fathers and theologians over the centuries offering various interpretations of their symbolic presence in the Nativity story.

Furthermore, if we consider the actual circumstances logically, it seems probable that when Joseph and Mary arrived, the cave was… empty.

Understanding the nature of this cave is crucial. Professor Alexander Lopukhin, in his “Interpretation of the Holy Scriptures,” explains, “The New Testament’s reference to a manger, a place for cattle feed, suggests that the Virgin Mary and Joseph found shelter in a cattle pen attached to an inn. With all rooms taken and the common area unsuitable due to Mary’s impending labor, they were lodged in this enclosure. According to ancient texts, this pen was within a cave not in, but near Bethlehem” (citing Justin the Philosopher’s “Dialogue with Trypho” and Origen’s “Against Celsus”). Thus, Lopukhin posits that this cave, adjacent to an inn, housed animals brought by travelers to Bethlehem.

Another perspective is offered by St. Demetrius of Rostov. He describes a cave to the east of Bethlehem, near the well of David, embedded in the stone mountain upon which Bethlehem sits. This cave, belonging to Salomia, a Bethlehem resident and relative of both Mary and Joseph, served as a refuge. Unable to find lodging in the crowded city, due to the influx of people for the census, Joseph and Mary sought refuge in this cave, as there was “no room for them in the inn,” especially as evening approached.

Thus, according to St. Demetrius of Rostov, Mary and Joseph, after finding no space in the inns of Bethlehem, logically retreated to this familial cave, a shelter typically used for cattle.

Tracing the Journey of the Ox and the Donkey to Bethlehem

The presence of the donkey and the ox in the Nativity scene is not just a picturesque detail but a narrative enriched with profound symbolism.

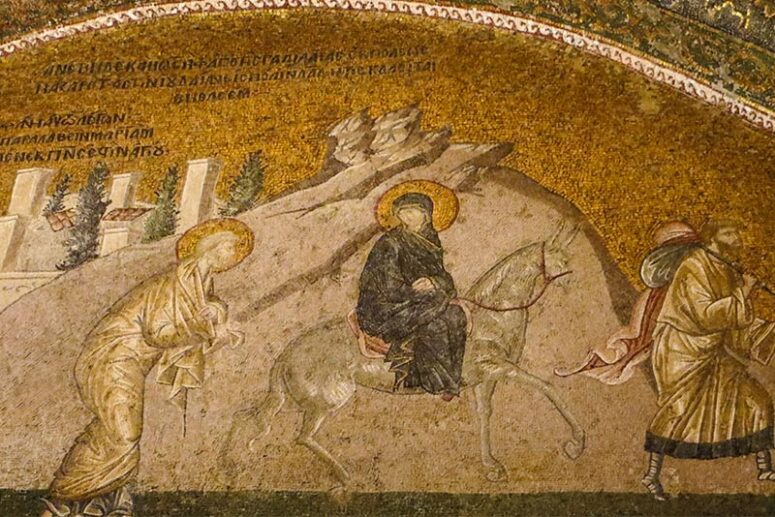

Joseph, a carpenter, and his betrothed wife Mary were temporarily residing in Nazareth. Though both natives of Bethlehem, the census compelled them to return. Alexander Lopukhin insightfully notes, “Mary’s advanced pregnancy was the primary reason Joseph could not leave her alone in Nazareth for an extended period. The journey to Bethlehem was long, and in Nazareth, she would have been defenceless.”

The three-day journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem was a challenge for Mary, given her condition. Therefore, she was carried on a donkey. Whether the animal was owned or borrowed by Joseph is uncertain, but it is clear that this donkey accompanied them from Nazareth.

The ox’s presence, however, is intriguing. St. Demetrius of Rostov suggests that Joseph brought the ox to Bethlehem intending to sell it. This was to pay the tribute demanded by Caesar and to cover essential expenses. Archimandrite Nicephorus Bozhanov describes Joseph as “a righteous and pious man living a modest life in Nazareth, sustaining himself through hard work.” The ox, then, was a crucial asset for the elderly carpenter to fund the unforeseen journey and stay in Bethlehem. The sale of the ox possibly facilitated the Holy Family’s move into a house, as the Gospel of Matthew recounts the Magi visiting them in a house, not a cave (Matthew 2:11). This suggests that after the initial rush of the census, Joseph was able to provide a more comfortable dwelling for Mary and the newborn Jesus, likely financed by the sale of the ox.

The Nativity Scene and its Symbolic Animals

Returning to the creche at the moment of the Nativity, St. Demetrius of Rostov poignantly describes the ox and the donkey warming the Christ Child with their breath in the cold of winter, serving their Lord and Creator in humble reverence.

In the Holy Scripture, every detail carries multiple layers of meaning. Although the New Testament does not mention these animals, the Old Testament does. Isaiah’s prophecy vividly states: “…the ox knows its owner, and the donkey its master’s crib; but Israel does not know, My people do not understand” (Isaiah 1:3). Thus, on Christmas, this prophecy finds its fulfillment: the animals bowing before Christ symbolize both the Gentiles (the donkey) and the Jews (the ox). St. Augustine of Hippo elaborates on this symbolism: “In the person of the shepherds and wise men, the ox has recognized its owner, and the donkey its master’s manger. The Jews, symbolized by the horned animal, were unwittingly preparing the horns of the cross for Christ. The Gentiles, represented by the long-eared animal, were prophesied to obey swiftly: ‘A people I have not known shall serve me. As soon as they hear of me they obey me’ (Psalm 17:44-45).” In the humility of the manger, the ox and the donkey, representing Jews and Gentiles alike, found their sustenance in the Word made flesh.

Exploring the Symbolic Presence of Animals in the Nativity Scene

The presence of other animals traditionally depicted near the Nativity crib is a matter of artistic interpretation and theological symbolism.

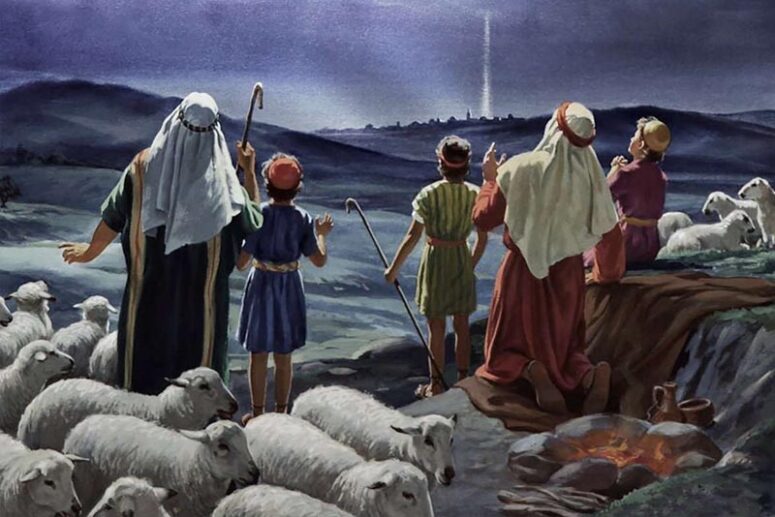

Sheep may have been present, not at the exact moment of Christ’s birth, but shortly thereafter. St. Luke the Evangelist notes: “Now there were in the same country shepherds living out in the fields, keeping watch over their flock by night” (Luke 2:8). The Messiah was believed to be born in the “tower of the flock” near Bethlehem, where sheep intended for temple sacrifices were herded. The shepherds, possibly connected to the Jerusalem temple, were chosen by the angel of the Lord to herald a new era – a time when sacrifices would cease, as the Son of God Himself would become the ultimate sacrifice. If these shepherds brought their flocks to the cave, the lambs there would also witness their Saviour.

Alternatively, the angel’s announcement to the shepherds could symbolize the Saviour’s preference for the humble and pure-hearted over the wealthy and influential. This aligns with the portrayal of Christ as both the Great Shepherd and the Lamb.

In some Nativity scenes, a dog is included. While it may seem unusual, shepherds have long relied on dogs for guarding their flocks. Aleksey Uvarov, in his book on Ancient Christian symbolism, notes that early Christian grave monuments often featured images of dogs, symbolizing fidelity to Church doctrine and vigilance against heresy.

Other creatures frequently depicted include doves, representing the Holy Spirit, and roosters with hens and chicks, with eggs symbolizing life and resurrection. Occasionally, camels appear, reflecting the journey of the Magi who brought gifts from the East, as foretold by Isaiah: “The multitude of camels shall cover your land… they shall bring gold and incense, and they shall proclaim the praises of the Lord” (Isaiah 60:5-6).

Thus, in the Nativity scene, every creature finds its place and meaning, embodying the universal joy of Christ’s birth. As the Matins hymn of the Nativity Feast proclaims: “Today every creature rejoices and is glad because Christ was born of the Virgin Mary.” This joy transcends the human realm, encompassing all of creation – people, animals, and heavenly beings. Christ is born, glorify Him!

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://foma.ru/vol-osel-ovechki-kak-oni-na-samom-dele-okazalis-u-yaslej.html

Thank you for this beautiful and educational email, really interesting!