Icon painting has deep roots in the doctrine of the Orthodox Church, but its artistic tradition originates from ancient art. No cultural phenomenon begins from scratch. None appears out of thin air.

To appreciate and interpret a work correctly, one needs to be aware of the cultural context. The early Christian icon painters were children of their time in one way or another. They developed their style and techniques in the context of the artistic tradition that existed around them. Our exploration of the old tradition could shed light on its influences on early iconography.

Hellenism

Despite its regional variations, the art of Ancient Rome grounded itself in the tradition of Hellenism.

Its formation coincided with Alexander the Macedonian’s raids to the East. The Greek states that came into being as a result created the environment in which the culture of the captors mingled with that of the local people. Hellenism was the product of this mingling between Greek, Egyptian and Persian traditions. Having captured most of the Hellenic states, the Roman Empire also came under the influence of Hellenism. The unique combination of Western and Eastern art forms also gave rise to the rich art tradition of the Byzantine Empire.

For many years, ancient sculpture and architecture remained the only artefacts of ancient Greco-Roman art known to most of the world. As for Hellenic fine art, we know their masterpieces from written descriptions and the surviving frescos on the architectural monuments of Ancient Rome or the painted images on the ancient vases. With a growing number of artefacts uncovered by archaeologists, our knowledge of ancient art traditions increased, and our understanding deepened.

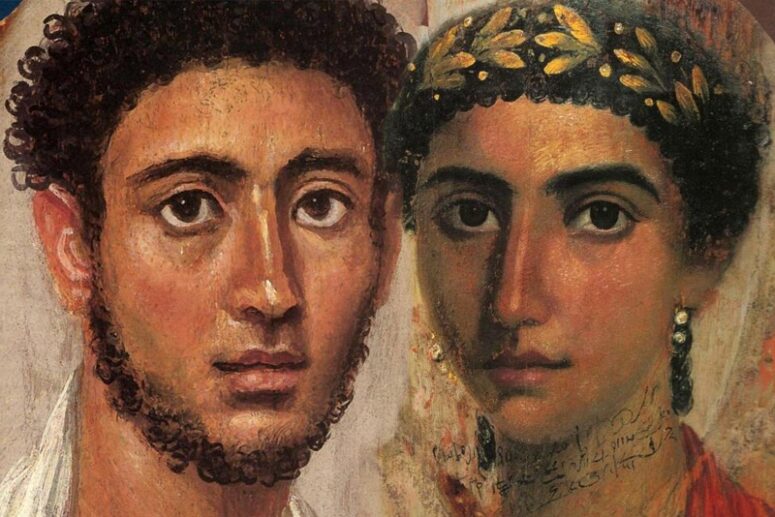

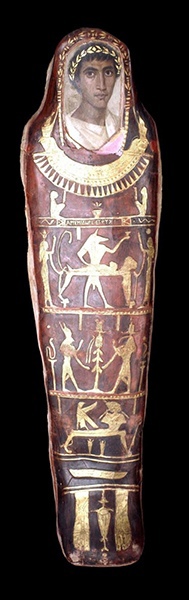

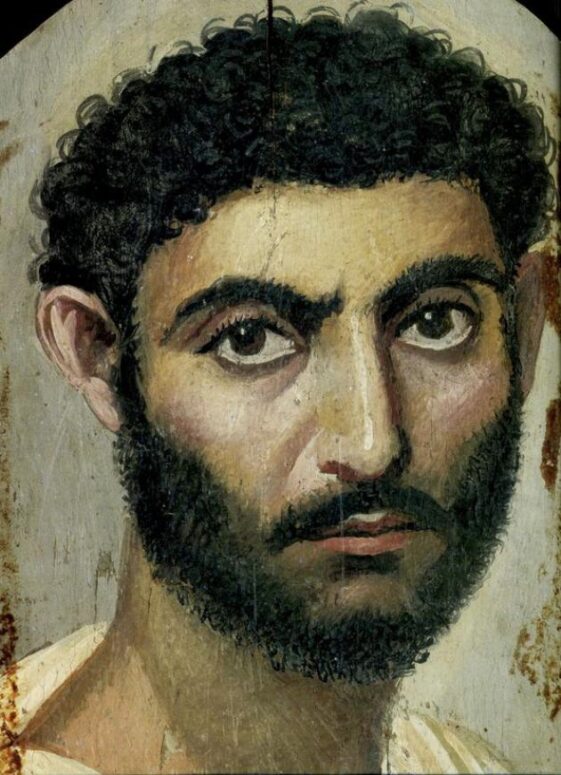

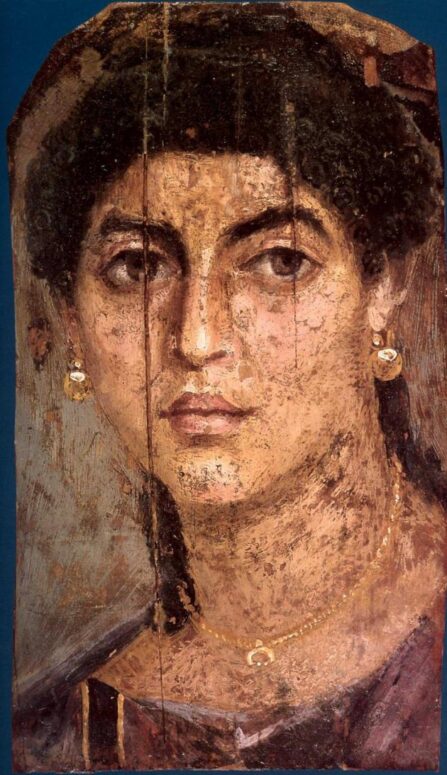

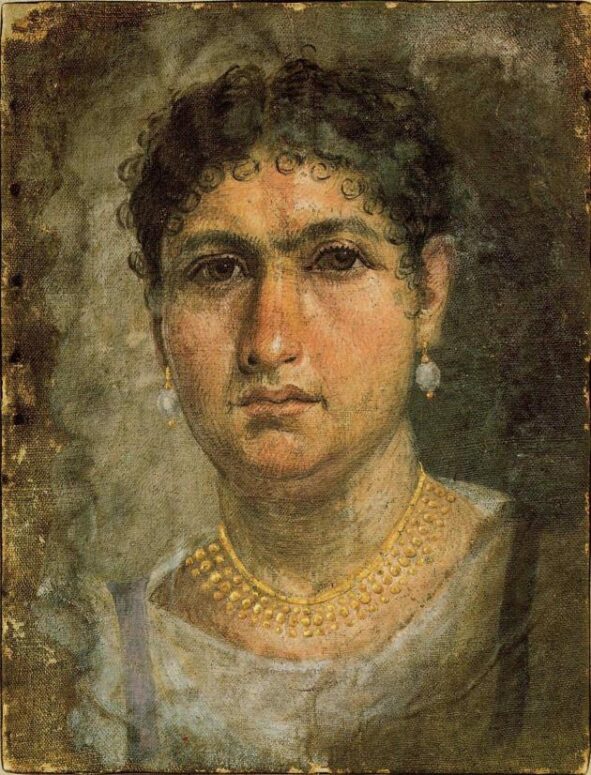

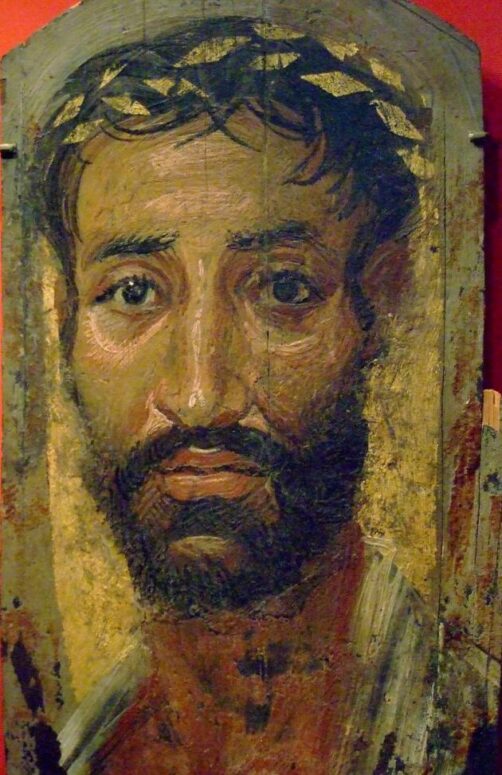

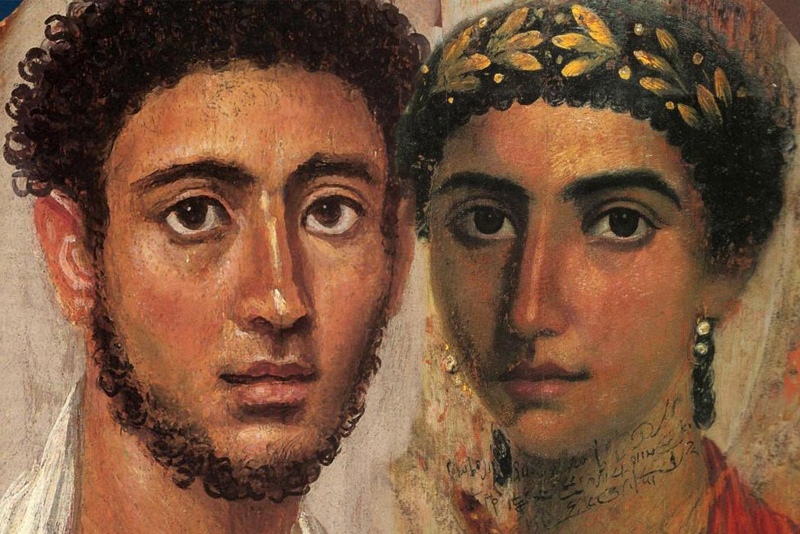

The discovery in Egypt of a half-ravaged collection of ancient works was a turning point. In 1887, archaeologists found in the Fayum Oasis mummies that looked different from the previous discoveries. Traditionally, Egyptian mummies were put in a case or a sarcophagus with masks that represented the facial features of the deceased. The mummies of Fayum bore no masks. Instead, they had the painted portraits of the dead. These portraits produced a fundamental change in our understanding of ancient art. Even today, they continue to surprise us.

The first discoveries were made near the present-day village of Er-Rubayat (close to the ancient city of Philadelphia). More paintings were found a few years later a short distance away, in Hawara Area, at the site of an ancient cemetery of Arsinoya, previously called Crocodilopolis. Because the majority of the discoveries were made around the Fayum Oasis, they were collectively referred to as Fayum portraits. In later years, similar works were unearthed in other locations, including Memphis, Antinople, and Fives among others.

Some 900 portraits have been discovered to date. Nearly all date back roughly to the 1st – 3d centuries AD, the period of the Roman conquest of Egypt. For several centuries before that time, Egypt had been ruled by the Greek dynasty of Ptomelei, descendants of a brother in arms of Alexander the Macedonian. The ruling dynasty was Greek, and so were the ruling elites. It was no coincidence, therefore, that the art of the Greeks coexisted with the local tradition. Hellenistic art was the product of their combination.

It affected various aspects of Egypt’s cultural and religious lives, including the funeral rites. Some examples of their depictions have survived our time. Some artefacts follow the old Egyptian tradition (mummies with funeral marks), others the newer Greco-Roman one, with funeral portraits.

Why are the Fayum mummy portraits interesting to Christians?

What is the reason for our interest in the Fayum portraits? Is it just their beauty? What makes them so notable to us, despite a variety of other artistic traditions of equivalent beauty?

As different from the other art forms, Fayum mummy portraits were not painted to be looked at (although their models were mostly living people), but in the context of the funeral rites. We are aware of the immense significance attached in Ancient Egypt to matters of the afterlife, and the funeral portraits were a crucial element of this culture. Ancient Egyptians believed in the ability of the spirit to incarnate as the portrait of the deceased and find a new life in it after separating from his body. It was with this possibility in mind that Ancient Egyptians painted the portraits. The artist had to strive for near-perfect similarity of the image to the deceased, or else the spirit may not recognise the portrait and be doomed to roam the earth without an abode.

Looking to eternity

Fayum portraits were more than depictions of a person or their exact copy at a particular moment in time. They depicted their model from the perspective of eternity. The focus of the artist was not just on physical appearance, but also on the ‘soul’ of the deceased (despite the difference in the meaning attributed to this word from its sense in the Christian doctrine). In most respects, therefore, the Fayum portrait is the depiction of the immortality of a person, and this emphasis on immortality likens it with an icon. Acknowledging the role of ancient philosophy in preparing the ground for theology, we often refer to Hellenic philosophers as Christians without Christ. Similarly, the Fayum portrait may merit the definition of an icon before iconography.

Composition

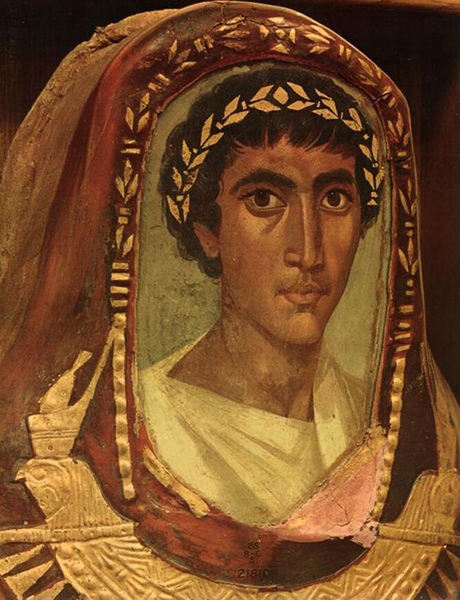

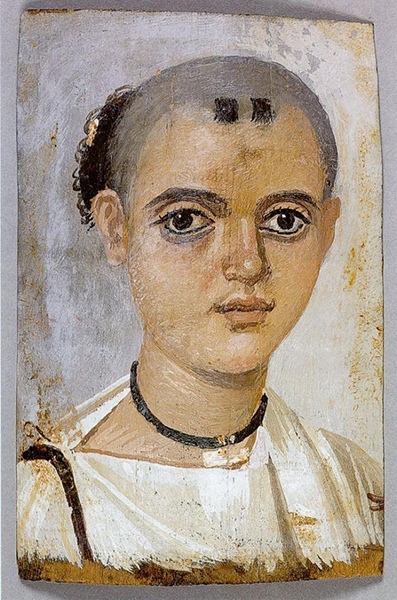

In the majority of the Fayum portraits, the figures are presented as busts (waist-length depictions are relatively rare).

The figures are shown from an angle turned three-quarters from the full face. Full face portraits are infrequent. The figures look straight or above the viewer. Light comes from above and slightly left of the figure. The right side is typically in the shade, regardless of the direction of the model’s turn. A dark wide stripe depicts the shadowed side of the model’s nose. The expertise in the use of light and shade is also visible in the more flattened portraits.

The faces show no emotion. The eyes are wide open. The models are shown against a monochrome background, typically in a golden or light colour.

One common feature of most portraits, particularly the later ones, is asymmetry. The left side of the face is different from the right in size, detail, level, height, or angle of depiction. Asymmetry was not an attribute of Hellenic art per se, but rather a new fashion of the time. For many artists, it was a way to underline volume and perspective.

Later, many iconographers used similar devices

In terms of techniques, the Fayum portraits displayed proximity to Christian icons, (as already discussed) Most Fayum portraits were painted on wooden boards, and some on grounded canvas. The predominant technique is encaustic painting (using wax-based paints), as with the first icons.

That the Fayum mummy icons could be the predecessors of Christian icons could be a shaky proposition to some who are prone to viewing them as a local and contextual phenomenon. However, the Fayum portraits are not a purely Egyptian phenomenon but are a part of the broader Greco-Roman tradition. Mummy paintings were localised to Egypt, but a similar painting tradition existed elsewhere in Rome. Funerary portraits of emperors and magistrates were found in the atria of the homes of the Roman upper classes identical in style to the funerary portraits from Egypt. Admittedly, examples of such artefacts are not numerous. The artefacts from the Egyptian burial sites have preserved examples of an art tradition that did not survive elsewhere.

Many centuries later, they continue to amaze. To many, they resemble their contemporaries. They speak of eternity. We can read it in the eyes of the figures.

Translated by The Catalogue of Good Deeds

Source: https://pravlife.org/ru/content/fayumskiy-portret-ikona-do-ikonopisi

There’s something missing in this paragraph:

Its formation coincided with Alexander the Macedonian’s raids to the East. The Greek states that came into being as a result created the environment in which the culture of the captors mingled with that of the local people. Hellenism was the product of this mingling between Greek, Egyptian and Persian traditions. Having captured most of the Hellenic states also came under the influence of Hellenism. The unique combination of Western and Eastern art forms also gave rise to the rich art tradition of the Byzantine Empire.

Yes, you are right. Thank you! We’ve fixed this mistake.

I’d like to use the image of the boy with two forehead tufts of hair. HOw do I obtain permission?