The scale of the persecution that the Russian Orthodox Church faced in the twentieth century can best be compared with the first centuries of Christianity, when the pagan Roman authorities were officially persecuting and killing Christians for their faith and their convictions. The number of churches in the Russian Empire reached 54,174 in 1914. It began to decline sharply after the communists came to power, declaring militant atheism as their state ideology and drawing the sword against parishes, churches, monasteries and clergy. In 1930 there were about 37 thousand churches in operation; in 1938 there were only 8302 and in 1941 this number declined to 3021-3732 churches. 1937 with 31,359 believers arrested only in the period from August to November (of whom 13,671 were sentenced to death) was the bloodiest year in the history of the Russian Church of the twentieth century. According to general estimates, 80 to 85% of priests (more than 45 thousand people) were arrested or executed between 1931 and 1941.

Clearly, the statistics don’t even begin to describe the horror and pain that these innocent people must have experienced. We must remember however that behind each figure there is a history of confession and martyrdom, human feelings, destinies and, most importantly, life and death. The following story of a simple rural priest who remained faithful to Christ and His Church, will certainly appear wild and heartrending, an iniquity that has no place in modern history. At the same time, people are still alive who remember the times when such cases (as terrifying as it may sound) were common and took place regularly.

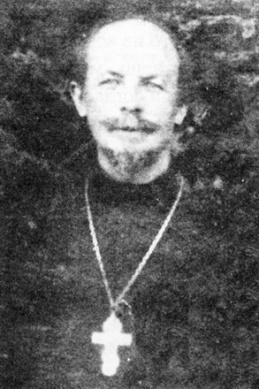

Hieromartyr Peter Grudinsky (born 1877) came from a simple peasant family. After receiving his education, he served as a municipal clerk for some time. In 1907 he was elected to the second State Duma of the Russian Empire where he represented the interests of the peasantry. After the October Revolution, in 1921, when the persecution of the Church had already begun, he was ordained a priest to the church in honor of St Nicholas the Wonderworker in the village of Timkovichi.

In 1930 he was arrested on the false accusation of anti-Soviet agitation, widely used at that time against believers and clergy. Father Peter received an offer to renounce his faith in exchange for saving his life, which was also part of the Soviet authorities’ usual practice. This trial was complicated even more for Father Peter by the pressure from his family (also greatly influenced by the government agencies). Correspondence was preserved between Fr Peter and his wife, Irina. This is what Irina wrote to her imprisoned husband,

“I beg you… if you have pity for me, give up your beliefs that do no good to anyone. I have asked you about this many times before. Think about how many scandals we had in eight years, fighting almost every day on the basis of religion! I was forced to be insincere with you and put on a mask because of my affection for you. I am tired of bearing the burden of something that I don’t believe in and I have no more strength. I ask you for the last time: who do you prefer – the real me or your evanescent ‘idea’?! If you agree with me, I will go to the ends of the world with you, not fearing any difficulties. But the thought of you continuing to be a priest makes me shudder. I cannot go on like this. Tell me, what am I to do?”

It is inconceivable what the spouses must have been experiencing in such a situation, especially Father Peter, who was under pressure and torture, the greatest of which for him was the letter that he received from his wife. The strength of the hieromartyr’s faith and his fortitude that helped him hold his ground despite all the trials are truly striking. Below is his answer to his wife,

“Dear Irochka, your letter struck me more than the arrest, and only the knowledge that it was dictated by grief and need, somewhat relieved me. For twenty-four years now we have been living together, and you, dear, had the opportunity to make sure that I always tried to be honest and fair, and that I never made deals with my conscience. You know very well that I have never been an enemy of the Soviet regime … and I do not consider myself a criminal in any way. There is therefore nothing to worry about. If life wants to put me to a test, then I need to stand up to it somehow. I have never “bound” my conscience, and I am surprised that you seem to be taking advantage of these disastrous circumstances to push me to a dishonorable act. I think that you know like no one else that my religiosity is rooted deep inside me and has never been feigned. Denying faith in Christ, Who makes up the meaning of my whole life and from Whom I have seen so many blessings; leaving Him as I am approaching the grave is something that I cannot and will not do, even for the sake of you, whom I love and always have loved. My dear, try to pull yourself together and don’t let black thoughts in… Please send me the comb, it is in my warm cassock. I am healthy and feel okay, except when I think about you and how difficult this must be for you. I hug you tightly, kiss you and pray that the Lord will strengthen you and keep you from evil”.

Like many of his contemporaries, Fr Peter showed a truly Christian steadfastness in faith, preferring eternal life to earthly safety. The death sentence that he met with dignity was soon carried out. In 1989, Hieromartyr Peter was rehabilitated by the Prosecutor’s Office of the BSSR. In 1999 he was canonized by the holy synod of the Belarusian Orthodox Church as a locally revered saint, and in 2000 he was canonized for general church veneration by the Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church.