Blessed Xenia of St. Petersburg, canonized in the late 20th century, is a venerated figure known for her devout life in St. Petersburg. Yet, a fascinating piece of art history tied to her legacy remains largely unknown to many of her devotees in the city. Within the prestigious State Hermitage Museum lies a portrait long believed to capture Blessed Xenia herself. This assumption, however, has been debunked in recent years, revealing a captivating narrative about the true identity of the ascetic depicted and their connection to the revered saint.

The Painting’s Journey

The mysterious portrait, attributed to an unidentified artist, bears the inscription: “Blessed Xenia / Obtained Smolensk Cemetery / Morozov, 26/ 09/1930”. Its discovery in 1930 by Fyodor Morozov, a State Russian Museum employee, a connoisseur of ecclesiastical art and formerly a novice of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, marked the beginning of its intriguing story. Morozov stumbled upon the painting in the Smolensk Orthodox Cemetery in Leningrad, under circumstances that hint at its cherished status among the faithful.

Evident soot marks suggest the longstanding presence of a candle or lamp before the painting, indicating it was an object of veneration. The portrait, likely encased in glass and housed within a custom frame, shows signs of meticulous preservation and multiple restorations throughout its history.

In 1930, this enigmatic artwork was incorporated into the Historical and Household Department of the State Russian Museum. It underwent further restoration, was copied, and then mounted on a cardboard base, continuing its silent witness to history and devotion beyond the life of the saint it was once thought to depict.

The Enigmatic Image

The subject of the portrait is garbed in a simple, light-colored shirt of homespun fabric, adorned with a cross on the chest. Dmitry Gusev, a researcher at the State Hermitage Museum’s Department of Russian Cultural History, notes the artwork’s rudimentary style and composition, hallmarks of its creation by a self-taught artist and a classic example of naive art.

At the heart of the portrait is the cross, symbolizing the depicted figure’s commitment to a Christian life of spiritual endeavor. The portrayal eschews any hint of madness, instead conveying a sense of serenity, resilience, and humility. The facial expression combines austerity with gentleness, capturing the essence of the saintly figure.

Nikolai Malinovsky, a restorer of the portrait, describes the artist’s approach as spontaneous, executed with swift confidence, likely in a single session. Despite lacking formal training, the creator of this work might have shared techniques with icon painters, suggesting a background in religious art rather than secular portraiture.

The Portrait’s Journey to Recognition

Initially housed within the State Hermitage Museum in the 1940s, the painting underwent its latest restoration in 2016. This process, coupled with scholarly research, dated the piece to the late 18th or early 19th century. Fyodor Morozov’s influence had long cemented the belief that the portrait depicted Xenia of St. Petersburg, though it was conjectured to have been painted posthumously, inspired by the artist’s impressions or accounts from those who had known her.

The portrait emerged from the storerooms to the public gaze in 2017, showcased in one of the Hermitage’s galleries. This exhibition sparked the first seeds of doubt regarding the true identity of the figure immortalized in the painting, leading to a reevaluation of its historical and spiritual significance.

Resolving the Portrait’s Mystery

The long-standing belief that a portrait in the State Hermitage Museum depicted Blessed Xenia of St. Petersburg was challenged by artist Alexander Prostev. He noted discrepancies between the historical descriptions of Xenia and the figure in the painting, particularly the clothing color and hairstyle, which did not match Xenia’s known attributes.

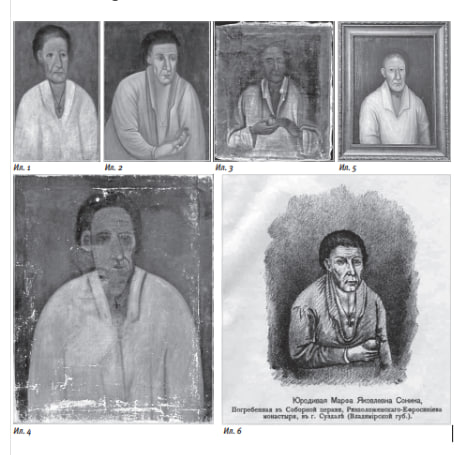

The mystery began to unravel thanks to the digital age’s connectivity. Social media discussions pointed to similar graphic types in the State Catalogue, drawing the attention of Hermitage staff. The decisive moment came when Julia Rogova of the Religion Museum discovered an 1893 publication featuring the portrait. It explicitly identified the subject as Marfa Yakovlevna Sonina, a Suzdal ascetic, thus redirecting the narrative towards this lesser-known figure.

The Legacy of Marfa Yakovlevna Sonina

Marfa Yakovlevna Sonina, recognized as a fool for Christ and residing near Suzdal in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, chose a life of spiritual devotion over familial ties. Despite the societal barriers preventing a poor girl from entering monastic life, she embarked on a pilgrimage, returning to live a life of asceticism and service in Suzdal. She was known for her prophetic insights and acts of healing, earning deep reverence both in life and posthumously.

Sonina’s Christian virtues were commemorated by a modest monument in Suzdal’s Deposition of the Holy Robe Monastery, where she was laid to rest. A belt portrait, once kept in the abbess’s cell, depicts an elderly woman with short grey hair, a simple white shirt, and holding an apple, capturing the essence of her ascetic journey. This historical correction enriches our understanding of the spiritual heritage preserved within the Hermitage’s walls.

Exploring the Iconography of Blessed Xenia

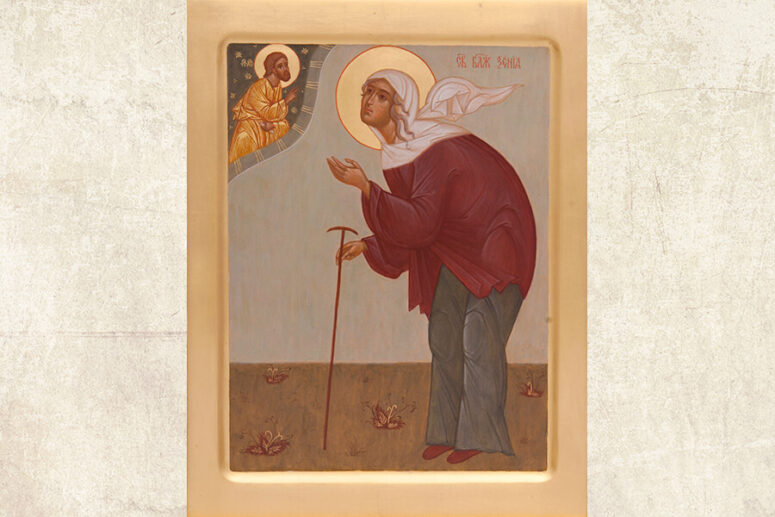

Blessed Xenia of Petersburg, canonized and deeply revered, boasts an iconography as rich and varied as her legacy, with over 90 distinct depictions contributing to one of the most diverse iconographic traditions for a saint of her standing. Commonly, these portrayals feature her full figure set against a church backdrop, clad in a soldier’s overcoat, often with a walking stick in hand or depicted in prayer. Beyond mere portraits, her iconography extends to hagiographic representations, capturing pivotal moments from her life—praying in solitude, wandering the streets in tattered attire, or facing mockery for her unconventional ways.

The iconographic legacy of St. Xenia evolved significantly in the 19th century, heavily influenced by the era’s artists who immortalized scenes from her blessed life. Despite the abundant imagery, the true likeness of Blessed Xenia eludes us, shrouded in the same mystery as the misplaced portrait in her name found at the Smolensk cemetery. The origins of this portrait, mistakenly attributed to Xenia and discovered by the collector Fyodor Morozov, remain an enigma. Morozov’s inscription linked the painting to St. Xenia, but the passage of time has obscured the reasons for its placement in the cemetery, the identity of its guardian for over a century, and the authentic appearance of St. Xenia herself—of whom no contemporaneous portraits exist.

What endures is the profound affection and reverence the people hold for Blessed Xenia, a sentiment preserved by the Church through tradition, safeguarded and transmitted across generations.

Traditional Iconography of Blessed Xenia

There are no less than 90 different types of images of Saint Xenia of St Petersburg, which makes her iconography one of the most diverse among the saints glorified in her rank. The most common depictions of the saint are full-length portraits against the background of a temple, where she is usually dressed in a soldier’s greatcoat, with a staff in her hands or in prayer. There are also icons with hagiographic marginal scenes. The iconography of St. Xenia developed under the influence of drawings by artists of the 19th century. Most often they represent scenes from St Xenia’s life, depicting the saint praying in the field or walking down the streets in shabby clothes, while the boys tease her for her strange appearance.

The painting is currently in the collection of the State Hermitage Museum. For the first time it was presented to a wide audience in the public area of the Hermitage’s restoration and storage center called the Old Village (currently the place of its permanent display) and the exhibition called Portrait Painting in the 18th – early-20th-century Russia in Vyborg (the Hermitage-Vyborg branch of the Museum) in 2017–2018.

Material compiled by the editorial team of obitel-minsk.org