Venerable Vincent of Lérins is a famous saint, who is Western by birth, but rather Eastern by spirit. In 2017, the Holy Synod of the Russian Church included the memory of this ancient Gallic saint in the church calendar. How did St Vincent glorify the Lord? What is his contribution to Orthodox theology?

Life

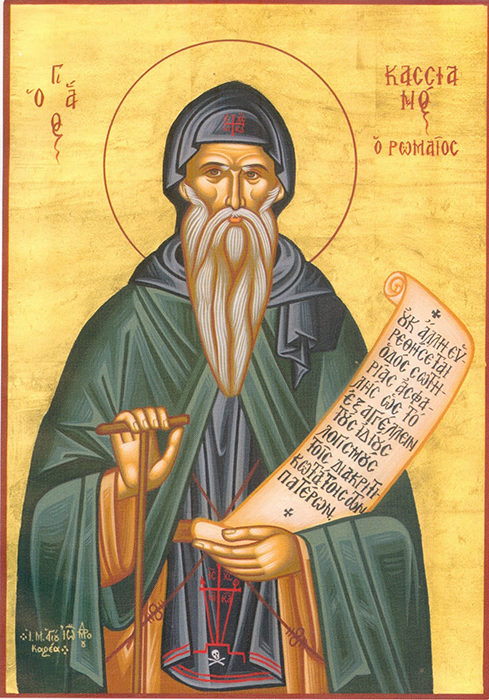

Information about the life of the Venerable Vincent (Latin Vincentius Lirinensis), in contrast to his theological views, is very scarce. Its main source is the work of the theologian and historian Gennadius of Massilia titled About the Renowned Men (lat. De viris illustribus), compiled around 495. The future saint was born to a noble Gallo-Roman family, most likely either in Toulouse or in Tula, a city in the former Roman province of Belgica (northeast of present-day France). It is also believed that he was the brother of St. Lupus of Troyes. St Vincent devoted his young years to a military career. Having served in the army for some time, he became disillusioned with the military craft and went to the famous Lérins Abbey founded by the Saint Honoratus, where he was tonsured and ordained a presbyter. Leading a prayerful and solitary life, Vincent comprehends the wisdom of Holy Scripture and participates in the riches of church tradition. His contemporaries speak of him as a man, outstanding in eloquence and knowledge. St Vincent died around 445, leaving behind him the composition titled Memoirs (Latin Commonitorium), written under the pseudonym Peregrinus (pilgrim). From it we can draw information about his theological views.

Triadology and Christology

St. Vincent of Lérins clearly formulates both the Trinity and Christological dogmas, exploring the church doctrine in his dispute with heretics. Reflecting on the Holy Trinity and Christ, the friar from Lérins links together triadology and Christology, thereby showing that all aspects of Orthodox theology are interconnected: «In God there is one substance, but three Persons; in Christ – two substances, but one Person. In the Trinity, “another” implies another Person, not another substance (distinct Persons, not distinct substances); in the Saviour by “another” is meant another substance, not another Person, (distinct substances, not distinct Persons) » (Common. 1.13).

St. Vincent traditionally explains the Christological dogma with a classical reference to anthropology: just as the body and the soul, despite being two different things, form one person, defining his dual nature, so in Christ, the Divinity and humanity are different in nature and yet form the same Christ in His two essences (Ibid.).

Tradition

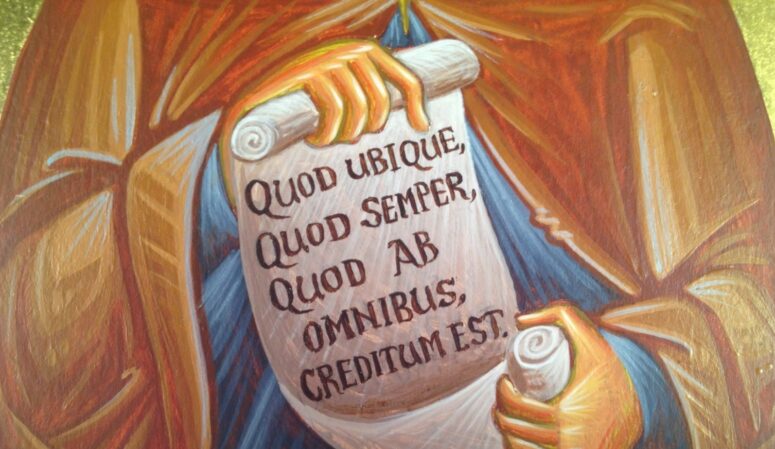

St Vincent is famous even more for his famous statement in the field of church tradition. In his search for criteria defining the true teaching, St Vincent comes to the conclusion that there are two: the correspondence of a specific teaching to the canonical books of Scripture and its loyalty to the tradition of the Catholic Church (Ecclesiae catholicae traditio – Common. 2 29). Scripture can be misinterpreted, therefore tradition is necessary, while in tradition itself we should adhere to “that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all”, i.e. observe the principles of universality, antiquity and agreement (Common. 1.2). Universality means recognizing the truth of only those provisions of the faith that are confessed in all Christian communities scattered throughout the Ecumene. Antiquity means following the faith of the apostles and their successors. The principle of agreement is to follow the definitions of all or almost all who are endowed with the priesthood and edifying duties, with priority to those fathers “who are living and teaching, holily, wisely, and with constancy, in the Catholic faith and faith communion, were counted worthy either to die in the faith of Christ, or to suffer death happily for Christ.” (Ibid. 1.28). General agreement is established by the unanimity of the great teachers of the church and especially by the dogmas affirmed by the Ecumenical Councils.

It is important to note that according to St Vincent, the principle of antiquity does not negate theological development. Development should consist in the internal sophistication of Orthodox doctrine, while remaining faithful to tradition and not changing the essence of faith. The Lérins Venerable compares that to the development of the human body, which, while remaining itself, goes through different ages. «Consensual and individual knowledge, wisdom and understanding of the whole church and of its every member ought, in the course of ages and centuries, to increase and make substantial and vigorous progress; but yet only in its own kind; that is to say, in the same doctrine, in the same sense, and in the same meaning.» (Common. 2.23). Such development can be observed in the conciliar activity of the church aimed at the consolidation of Orthodoxy and its struggle against fallacies.

Soteriology: the Controversy about Grace and Free Will

Finally, the saint is known for his stand on the question of grace and free will, where he shared teachings of St John Cassian and St Faustus of Regia, challenging some extremes found in the views of St. Augustine claiming that after the Fall, man lost the ability to desire and do good. It was these extremes that led St Augustine to the controversial doctrine of predestination to either salvation or corruption. St Vincent and the Lérins School of monasticism as a whole, criticized such views, believing that they lead to the idea that God does not want everyone to be saved, even if everyone wants to be saved (Prosper. Resp. Vincent. 2,7,8, 9) and that God created most of humanity doomed to eternal torment, which also disparages the saving Cross of Christ. Followers of St Augustine impotently accuse St Vincent of semi-Pelagianism (a doctrine that refutes both the heresy of Pelagius and the extremes of Augustinism), but in reality he is a supporter of the Orthodox doctrine proclaiming the synergy of God and man. Despite the catastrophic nature of Adam’s fall, putting us in need of the grace of God on the path to salvation, it could not completely overshadow the image of God in man, along with his desire and even the ability to do good, for “in every nation, he who fears Him and acts righteousness is pleasing to Him. “ (Acts 10:35).