For the Orthodox Church, taking a stance on religious sculpture has been no simple task. On the one hand, it seems at odds with the long-standing tradition. On the other, multiple sculptures of well-known saints have appeared in the streets of many Russian cities over the past two decades. So what is the tradition for depicting saints in the Orthodox Church, and where are its roots? Is there a place for the sculptures of saints in an Orthodox temple? Furthermore, what religious meaning, if any, should we ascribe to the statues of the saints outside the churches?

Sculpture in the early Western church

Early Christian church art evolved in the context of the ancient cultural tradition, where the sculpture was a prominent art form. The ancient tradition viewed the human body as a model of perfection, and the human being as the crown of nature.

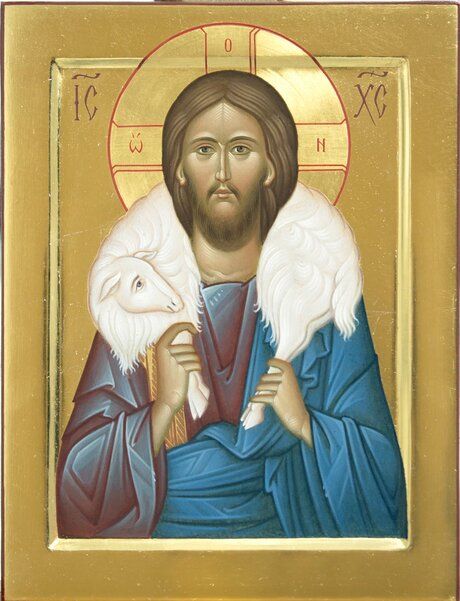

In the early centuries after Christ, veneration of the sculptures of Jesus Christ and His apostles became common among early Christians. For example, Eusebius of Caesaria writes about the stature of the Saviour in Paneade built by the haemorrhaging woman from the Gospel (Matthew 9:20 – 23). A sculpture of Christ the Good Shepherd was found in the catacombs of Rome.

The Christian worldview does not denigrate the physical body. On the contrary, Christianity teaches that we are all temples of the Holy Spirit. “Don’t you know that you yourselves are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in your midst?” (Cor. 3:16) At the same time, Christians understand that a person is not only a body, but also a Divine Spirit and an immortal soul. In an effort to communicate this through the visual arts, over time Christianity began to give preference to iconography and flat relief. It was iconography that became the primary pictorial language in the Eastern Church. In turn, the tradition of icon painting originates from the ancient Fayum portrait, which in turn evolved from naturalistic depiction to symbolism. The task of an icon is to portray the spirit, essence and inner being and provide a window on eternity.

The Epistle of St. Herman, which was read at the Seventh Ecumenical Council (the Saint’s name was inscribed in the diptych of saints for that council), clarifies the attitude of the Eastern Church towards both sculptures and icons. Although the veneration of sculptures was not reprehensible or forbidden, it was still associated with a pagan heritage. Icons, on the contrary, were perceived as a more sublime way of worshipping God. The mission of the icon is not to reflect the outward signs of human nature, but to reveal the spiritual world, serving as a window to eternity.

This well-established tradition was described in the mentioned epistle: “…The Lord did not reject what had been done according to the Gentile custom. He graciously showed through this statue (a/n: erected out of gratitude by the Gospel hemorrhaging woman) the miraculous work of His grace. In our tradition, however, this custom (a/n: painting icons) has taken a much more appropriate form.”

Thus, although the Ecumenical Council did not prohibit sculptural images, the cultural differences between the Eastern and Western Churches led them in two different directions.

Sculpture in Russia

With the Christianisation of Russia in the 10th century, the people began to see statues as Pagan idols to be cast away after baptism. It would indeed be strange for the Slavs to begin to venerate a different set of statues after abandoning idolatry. The Russian artists instead channelled their energy into iconography, frescoes and mosaics.

But the Russian church never rejected sculpture definitely. Some older churches were adorned with bas-reliefs, such as the Church of Saint Dmitry in Vladimir (1191), or the Church of Saint Georgias in Yuriev-Polsky. Yet these bas-reliefs did not yet meet the definition of sculptural images.

The first sculptural images in the proper sense of the word, taking the form of carved flattened relief on wood, appeared in the Russian churches around the fourteenth century. The carved images of Nicholas of Mozhaisk spread widely across the land, modelled on the depiction of Saint Nicholas of Bari. In the 15th century, Russia and Italy began to deepen their bilateral ties. Italian architects came to build the Moscow Kremlin, and Russians visited Italy and Bari. With reverence for Saint Nicholas, Russian craftsmen made copies of the Italian statue, often colouring them with paint, like icons.

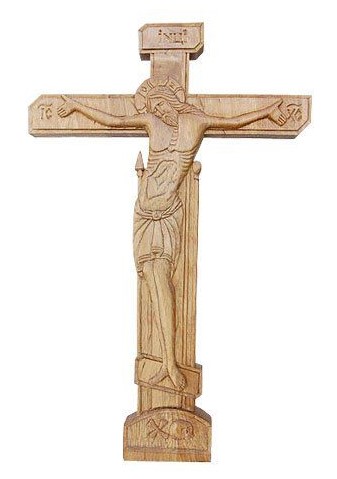

Hegumen Philip (Kolychev), who would later become a holy martyr of Moscow, carved from wood a figure of Christ and prayed before it in a chapel on Solovetsky Archipelago. According to a historical record, he finished the work in the 16th century after having a vision of Christ in shackles and a wreath of thorns. Furthermore, according to tradition, it was the hegumen’s decision to carve the sculpture of Christ. Perhaps he had more talent as a sculptor than as a painter.

For some time, carving remained popular in the North of Russia, but the depictions became progressively flat and emphasised the spiritual, rather than the physical.

Statues appeared in the Russian churches when Western influence reached its peak in the 18th and 19th centuries. One prominent example is the Church of Saint Isaac in Saint Petersburg, built in 1858, the interior of which is adorned with the statues of Christ, the saints and the apostles.

Wooden, bronze and masonry sculptures gradually appeared in central and provincial churches, but their relative number remained small. The baroque sculpture was still too remote from the perception of the Saviour and the Theotokos shared by most Orthodox. To the Orthodox eye, it was the opposite of the ideal of dispassionate contemplation of God described in the works of the Holy Fathers.

In his early 20th century memoirs, Bishop Nikon (Rozhdestvensky) thus described this perception as widespread among believers: “These carved figures put many believers in a depressed mood. I experienced it myself. The church authorities have decreed multiple times that such carved engravings be removed from public view, exempting only wooden crosses with artful engravings. However, these orders are frequently disobeyed, and some defenders of the old-time traditions asked the archbishops to preserve these antiques.”

From the revival of church life in the early 20th century to the present day, sculptures and statues in churches have not become any more common. The latter does not apply to wooden Golgothas, however.

Monuments to saints

The tradition to build monuments to saints came to Russia in the 19th century. The first such monument, to the Holy Prince Vladimir, appeared in Kiev in 1853. To the people today, it has become an integral element of the surrounding landscape. Back then, however, it met opposition from several hierarchs of the Church. When Philaret (Amfiteatrov), the then Metropolitan of Kiev, received an invitation to consecrate the monument, he refused outright. “It is not good to set up an idol to commemorate the works of the saint who was destroying idols.” But the Metropolitan’s objections were overlooked, and more monuments to saints were built, along with the statues of secular historical figures.

In Soviet times, monuments to Lenin and Stalin were put in the place of the monuments to saints. With the statues, the Soviets were promoting the personality cult of their leaders, reinforcing the perceived link between sculpture and idolatry.

In the church revival period after the demise of the Soviet Union, the main Christian monuments were churches. But the tradition of building statues of the saints also resumed. Sculptor Vyacheslav Klykov was one of its enthusiasts. He authored multiple known monuments to saints, including to Sts. Cyril and Methodius in Moscow’s Slavyanskaya Square, the Holy Royal Martyr Elisabeth Romanov outside the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent, and Sergius of Radonezh in Radonezh.

Statues of Christian saints

Today, more statues of the saints are appearing, including at monasteries and outside churches, and many are being consecrated. Yet there remain some open questions regarding the religious meaning of these statues. Should they be seen as objects of veneration, or simply monuments to the people they depict?

Bishop Nikon (Rozhdestvensky) writes, “The Church had built, and continues to build churches as monuments, but has never built monuments as secular statues.” “They entered the world by human vanity,” concludes the Bishop, referring us to Chapter 14 of the Book of Sirach. He explains that a Christian will see in human greatness a gift from God, while forgetfulness about God and fixation on the human genius as the source of all achievements is a refined form of idolatry. “The righteous do not need monuments to have eternal memory across generations,” he writes.

In turn, our contemporary Hegumen Luke (Stepanov) insists that we should not treat the monuments as objects of veneration, like icons, but only as an expression of our gratitude and love for the saints. Their significance is mostly cultural and educational — monuments keep our memory of the saints and outstanding persons who helped enlighten their countrymen and assert the Christian faith in Russia.

This is a very beautifully written article. God bless you! There’s a lot of crazy stuff on the internet and I’ve been overjoyed to find a blog so sober as this one.

As an Orthodox Christian in a city with only secular and (Roman) Catholic Universities, and being a student at the latter, would you suppose it’s imprudent for me to light a candle by a statue of the Theotokos as I pass by my University’s chapel? In any case, I’ve often thought statues to be untasteful but as of late have been trying to combat my prejudice after reading that the Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council defended the veneration of effigies.

However, I read in your article that, “The Seventh Ecumenical Council ended those disputes, ruling against the use in the worship of three-dimensional objects, or statues.” Yet, I’ve noticed that in worship, strictly speaking, I only venerate the Holy Chalice, the Gospel book, and on Holy Friday, the Epitaphios. Besides that I don’t notice myself venerating any icons – to say nothing of statues – when actually praying in Liturgy or Vespers.

Do you think the Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council prohibited venerating statues in general, or just during the Divine Services?

Thanks for your article!

– Tikhon

Dear Tikhon! Thank you for your comment. Unfortunately, the interpretation that we borrowed from another source cannot be called correct. We have reviewed the materials of the seventh Ecumenical Council, and indeed found no specific prohibitions on building sculptures in churches. This topic is mentioned in passing in the epistle of the Holy Patriarch Herman. It says that although the Lord did not reject the legacy of the pagan custom and even performed miracles through brass statues of God, Eastern Christianity (which later became Orthodox) adopted icons as a more “appropriate” form of representing the Lord, the Mother of God, and the saints. Thus, although the Council does not formally prohibit or condemn sculptures, the Catholic and Orthodox traditions have taken different paths in this regard.

There is nothing wrong with placing candles in front of a sculpture of the Holy Virgin, offering prayers and showing reverence for the Person, and not for the stone. In the centuries-old tradition of the Russian Orthodox Church, where in the 18th century there were indeed official bans on sculptures in churches, three-dimensional figures never took root. However, we do not think ill of them. As mentioned in the article, we sometimes erect monuments near churches and monasteries as a sign of special veneration and for silent education of the people.

We apologize if our article has misled you in any way; we have corrected the article.